How Hygiene and Medicine Defined Architecture: Hospital Modernism in the Case of the Tuberculosis sanatorium in Holosko

«Dodging through dirty, dusty streets, first by tram, then by bus, we leave the stale city air for the piney expanse of Holosko» – this is how an advertising report about the Holosko sanatorium in the newspaper «Gazeta Lwowska» from 1942 apparently begins.

- Constructed: 1930

- Style: modernism

The author of the article offers a trip to the “other world”, where you can not only get your lungs treated, but also take a break from the urban noise and chaos. The advice to “hide” from urban life in 1942, during the Nazi occupation of Lviv, sounds rather ambiguous, but ultimately it is about the treatment of tuberculosis (Gazeta Lwowska, 1942: 5).

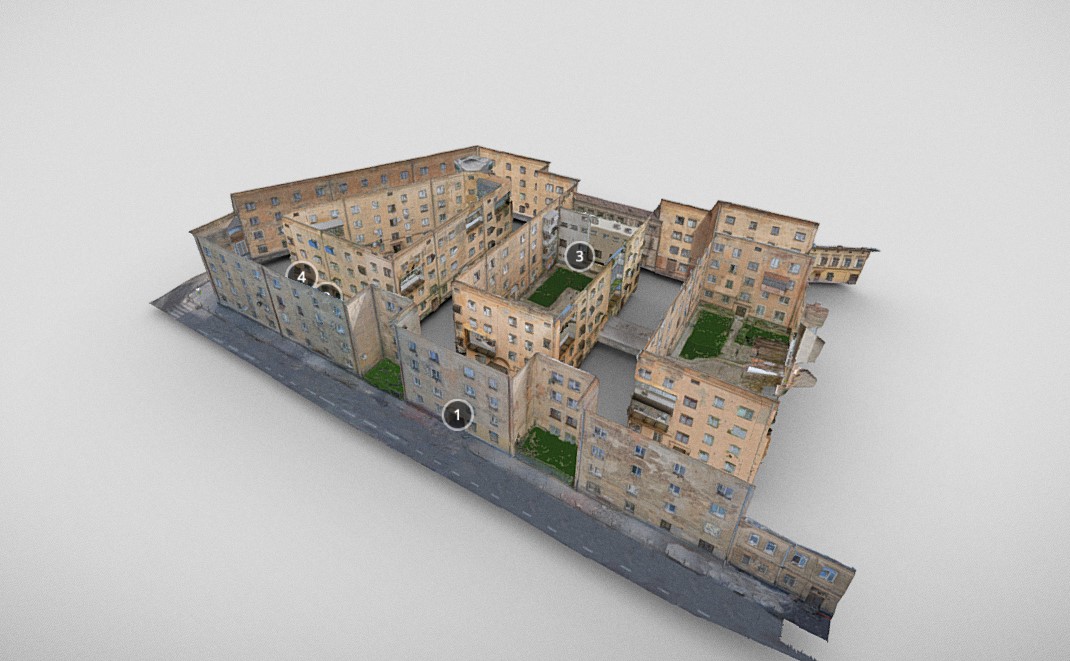

To get to the sanatorium, you need to go to the very end of Zamarstynivska Street (No. 274) and turn into the forest on the right. The road runs uphill, and first you see the old pavilions of the sanatorium, and then the newer, modernist pavilion.

By the way, architectural critics and theorists believe that it was the development of the medical system, technology, and the construction of medical facilities after the First World War that prompted many architects to design in the modernist style.

Back in the 1930s, some theorists and philosophers called modernism “hospital architecture”. This was because the white colors, matte tones, sterility, and strict adherence to function often resembled the design of post-war hospital wards, according to critics of modernism (Weizman, 2019: 43-45). Not only architecture, but also the furniture of modernism was inspired by the functionality of hospital style. If we look at Le Corbusier’s famous recliner chair, which the architect designed for private villas, and the recliner in a tuberculosis sanatorium, we can find similarities. In both cases, our bodies are exposed to certain breathing and sun exposure procedures, and in both cases we have a lot of light through huge windows and access to the sun.

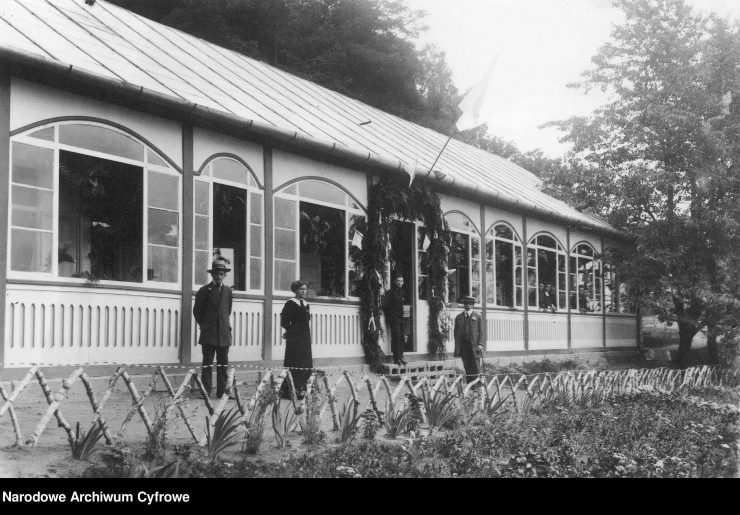

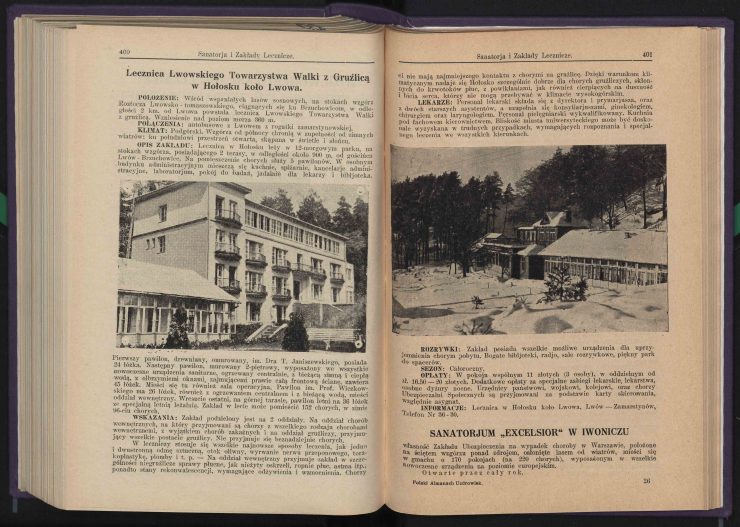

But let’s get back to the sanatorium in Holosko, which was founded on 11 July 1909. The initiator of the construction of the facility was the Lviv Society for the Fight against Tuberculosis (Lwowskie Towarzystwo Walki z Gruźlicą). The first pavilions of the sanatorium were opened on a hill on the side of the road leading to Bryukhovychi, open to the sun to the south and protected by a higher hill from the winds from the north. The administrative building was a separate structure. According to a medical almanac, the sanatorium was located in a foothill climate (Almanach Uzdrowisk, 1934: 400-401). The old pavilions (archival photo below) still exist.

At the end of the 20s, the sanatorium was modernized. The facility was electrified and equipped with central heating. At that time, there were already 3 pavilions, but there was still not enough space, so it was decided to increase the number of beds and build a new pavilion. In 1930, the sanatorium received a new building, and in 1934 it was renamed the Tuberculosis Society Hospital. Later, the institution was referred to in all media with both names (Pomeranian Journal of Life Sciences, 2017: 63-68).

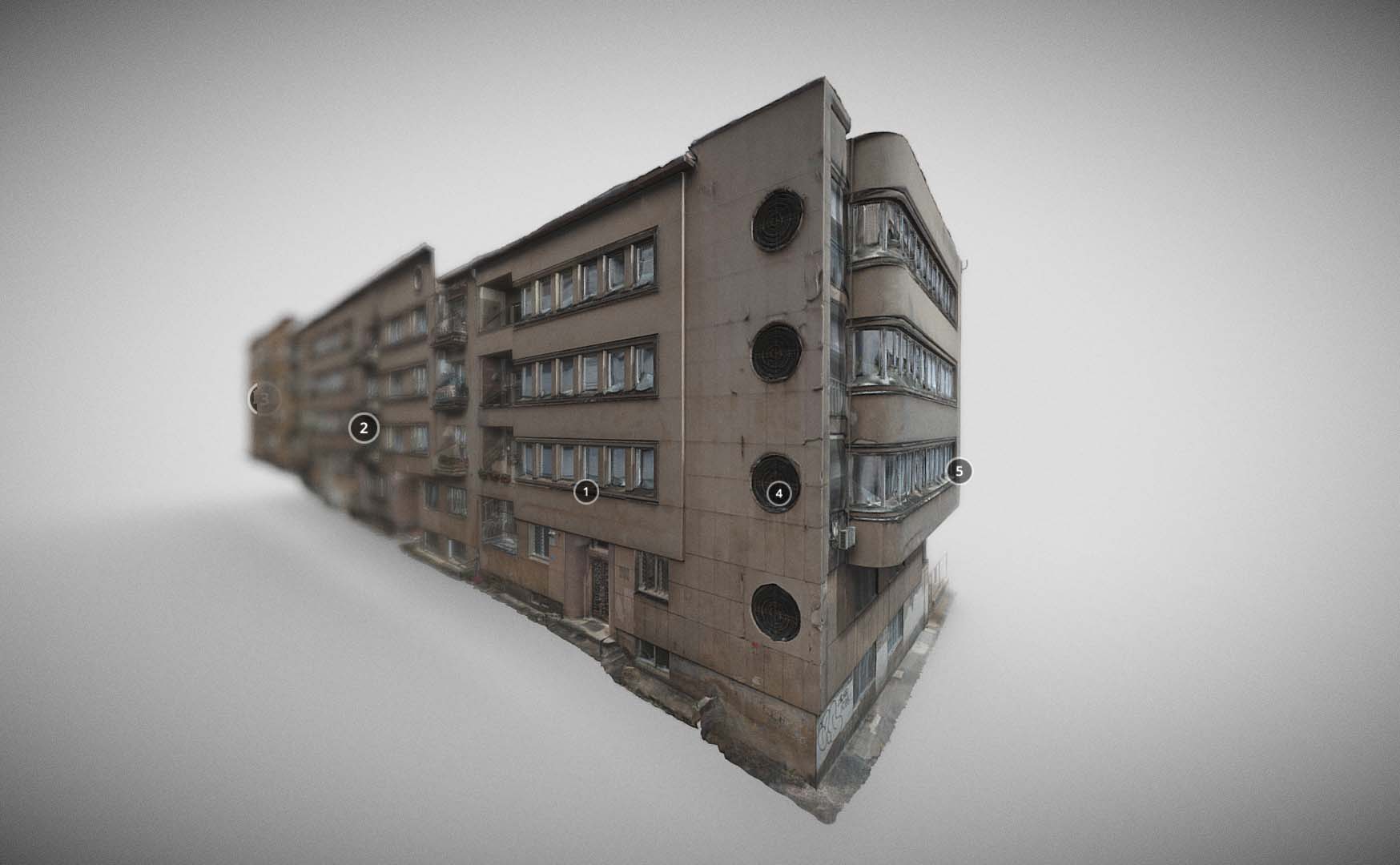

The pavilion was built on a mountain terrace. The building had 3 floors, the last one had a special summer terrace, which had the most sun and fresh air in the warm seasons (Chwila, 1933: 14). The façade was characterised by simple linear forms. Following the norms of sun and fresh air, the building was fitted with a number of large windows. According to doctors, dry fresh air and sunlight were the best procedures. By constructing this type of building, where it was possible to regulate access to air and sun, the medical system and architects were already resorting to a kind of climate control for patients.

The architects followed not only the function but also the aesthetics, so they added expressive triangular balconies to the façade. The staircase made of clinker brick and reinforced concrete, which connects the building to the lower terraces of the treatment area, also adds rhythm to the building. The purpose of the pavilion is obvious, as it was a summer retreat for a greater number of patients during the summer months. The summer terrace of the house had 36 beds, and the lower floors were used more in the winter. In total, the facility could accommodate 152 patients, and 96 in winter (Almanach Uzdrowisk, 1934: 400-401).

In general, the institution had two departments: one was for patients with various pulmonary and bronchial diseases, and the other was for patients with tuberculosis, but in mild stages. The patients were treated with procedural and surgical intervention (the sanatorium had a surgical hall), as well as with diet, sun and air baths, for which there was a suitable climate. To improve their health, the patients also worked in the gardens that were part of the sanatorium. For entertainment, patients had a library, a dance hall, a radio, and most importantly, a coniferous forest (Pomeranian Journal of Life Sciences, 2017: 63-68).

One interesting moment in the history of the sanatorium was the so-called “night sanatorium”, which was a treatment system for very busy people who cannot go on holiday or leave their workplace. Doctors’ examinations, procedures, and a full range of services were available from 6 p.m. to 8 a.m. for them. (Chwila, 1933: 14). As you know, during the Modernist period, various methods of recreation and recovery began to emerge to increase the efficiency of workers. We are now approaching the peak of this trend.

Because of its novel medical treatment and architecture, the Holosko sanatorium was often advertised in the press. Articles promoting the sanatorium emphasised that it was built on dry, sandy soils, so there would be no place for dampness (Wschód, 1937: 39). The authors also emphasised the cleanliness of the rooms. In fact, hygiene is perhaps the most obsessive feature of modernist architecture. Compliance with hygienic norms was linked to architectural inventions: more light and spacious rooms, less, and even a minimum of furniture, floor and wall coverings that were easy to clean.

In 1937, the Holosko sanatorium/hospital was included in an illustrated guide to Lviv. From today’s perspective, this looks rather strange: what would a nursing home do between stories about the best architectural monuments and entertainment in the city (Lwów, ilustrоwany przewodnik, 1937: 170). However, during the modernist two decades, the concept of a healthy person was just beginning to be embraced, so a sanatorium was as important as a visit to a sports event or a cathedral.

The 1937 guidebook emphasised that the Holosko sanatorium was on a par with similar Western European institutions (Lwów, ilustrоwany przewodnik, 1937: 170). The movement for the triumph of health and purity provoked the building of numerous modernist sanatoriums all over the world. For the most part, their descriptions and architectural forms would not differ much from those of the Holosko sanatorium.

Take for example the Paimio sanatorium (1929) designed by one of the most famous modernist architects in Finland, Alvar Aalto. It was built according to the same constructive principle, in the middle of a coniferous forest, with sunny terraces and a space that is as open as possible to cleanliness (Woodman, 2016). So, if Le Corbusier considered a house to be a machine for living, then we can call modernist sanatoriums machines for recovery.

Unfortunately, today the space looks abandoned. During the Soviet era, the sanatorium continued to operate as a children’s tuberculosis hospital, and since 2010 as a children’s TB department of the ENT facility of the Phthisiopulmonology Medical Association. The future of the sanatorium is unknown.

Sources and literature:

• Hołosko – znany ośrodek leczenia gruźlicy na kresach południowo‑wschodnich Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, Pomeranian Journal of Life Sciences, 2017: 63-68

• Gazeta Lwowska, 29 сzerwca, 1942: 5

• Chwila, 17 maja, 1933: 14

• Chwila, 17 wześnia, 1934: 4

• Wschód, sierpień – wrzesień 1937: 39

• Lecznica Lwowskiego Towarzystwa Walki z Gruźlicą w Hołosku koło Lwowa. In: Polski Almanach Uzdrowisk. Kraków: Polskie Towarzystwo Balneologiczne; 1934. p. 400-401

• Lwów, ilustrоwany przewodnik, 1937: 170

• Dust and Data, Ines Weizman, 2019: 43-45

• https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/revisit-aaltos-paimio-sanatorium-continues-to-radiate-a-profound-sense-of-human-empathy