About modernist architecture.

Modernist architecture encompasses a number of entwined styles. Some well-known examples are functionalism, Streamline Moderne, constructivism, expressionism, Art Deco, and many others. Modernism is often considered a style on its own.

Often, modernist architects were misunderstood or rejected. Architects that worked in totalitarian countries like Nazi Germany and USSR were met with difficulties and, later, persecution. Meanwhile, between WWI and WWII, other countries, especially the newly established ones like the Republic of Poland and Czechoslovakia, mainstreamed this architectural trend in their state policy.

Lviv and modernist architecture

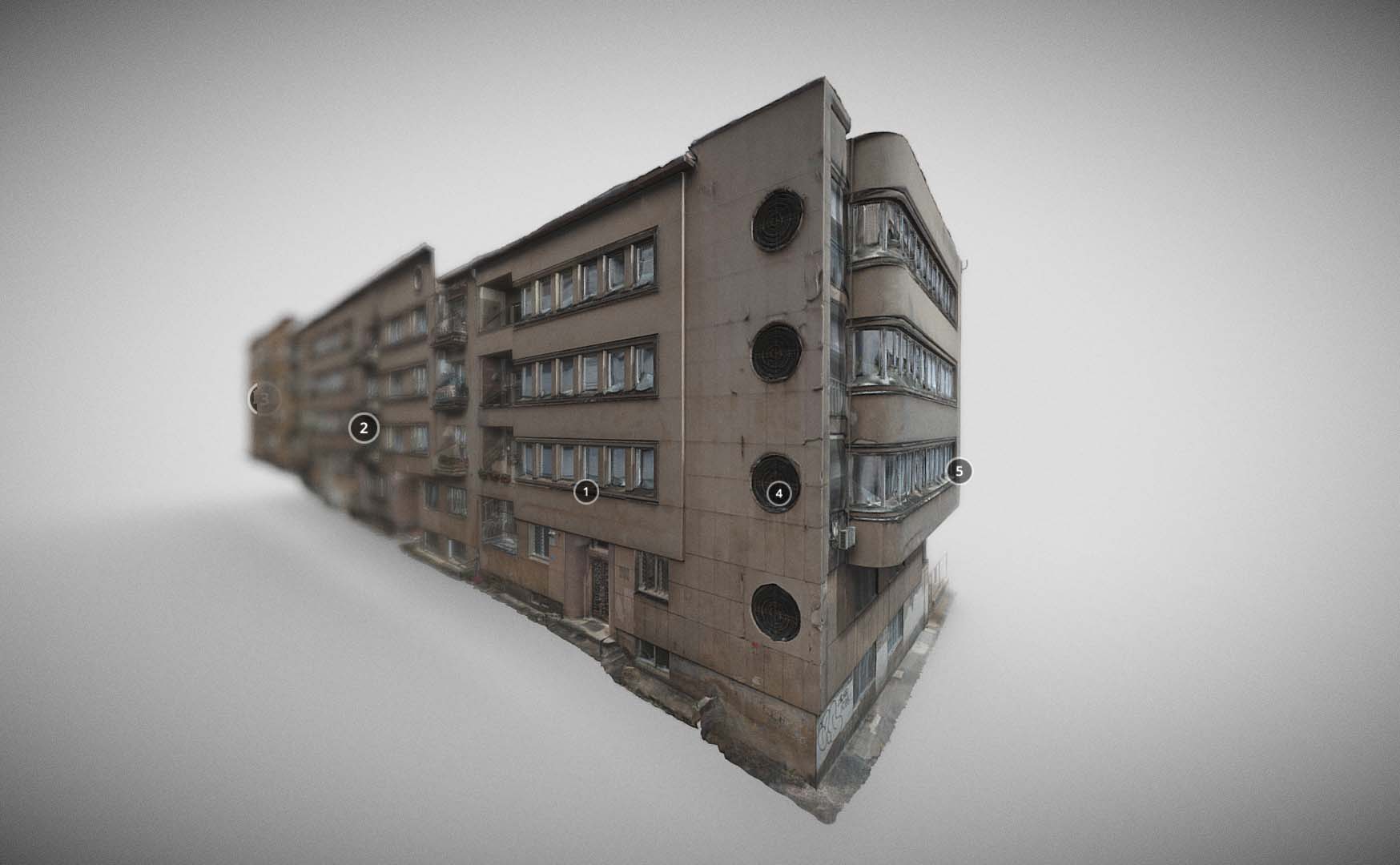

During the interwar period, Lviv, at the time a part of the Second Polish Republic, became a venue for bold modernistic projects. Resident architects got on board with this trend, which kept gaining popularity in New Europe. These architects abandoned lavish Secessionist designs, focusing instead on simple, geometric forms. Most modernist architectural buildings erected in Lviv reflect functionalism, but other styles were also employed. Lviv modernism also presented unique features based on ethnic motifs and original design solutions by Lviv’s architects. Modernist buildings in Lviv boasted particular types of plaster and rustication (décor elements in modernism) that are not found on similar buildings in other European cities. Even the worldwide Art Deco style had here its own distinctive features and the name ‘crystal style.’

Lviv wasn’t a part of the central industrial district of Poland, where the largest governmental investments were disbursed. So, the city did not have enough funds to undertake many state-led projects, especially in housing. With the exception of several social projects, it’s the middle- and upper-class housing that’s the most commonly represented in Lviv. The housing projects were often funded by private owners and large companies and less often – by labor coops or the government.

Wealthy residents of Lviv commissioned villas and revenue houses (rented apartments) in this fashionable style. Some prime examples include the notary office on Saksahanskyi St., 6; complexes on Doroshenko St, 47-59; Stryiska St, 36-42; Kyivska St, 24-28; villas on Halytska Armiia St (Hlynka St ) 12; Hipsova St, 36B; Hrytsai St, 4.

Lviv boasts entire streets, blocks, and neighborhoods built in functionalism or other modernist styles. Among them are Snopkisvka St or Konotopska St, whole blocks of streets like Kubiiovych, Tiutiunnyky, or Academic Pavlov and Tugan-Baranovsky. There are many neighborhoods in Lviv, wholly designed in a modernist style, like Kastelivka, Kviatkivka, Zalizna Voda, Professors’ settlement, officers’ settlements on Chereshneva St. and Odeska St., co-op ‘Vlasna Striha,’ and many others.

This fashionably popular style was employed in erecting education institutions, public recreation centers, office centers, sports infrastructure, and sacred buildings. These include the Sprecher House (now the Trade Unions House); St. Ursula's High School (now the Secondary School No. 28); the Academy of International Trade; the theater for the Jewish community (now the First Theater); the Church of Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn (now the Church of the Intercession), and many others.

The heritage of modernism holds particular value as an embodiment of innovation and the establishment of the modern world. Unfortunately, architecture and tangible artifacts are almost all that’s left to bear witness to the events of those days, as nearly 90% of the city’s population vanished during or shortly after WWI. As we delve deeper into researching buildings and tangible heritage, we not only bring to light architecture but also try to trace the lives of people who were somehow connected to these buildings and current residents’ involvement.