Rituals of habitation in Szymański villa: from 1930s to present

Each house has a story to tell, reflecting a city and country’s social and political changes like a mirror. Events lay on the surfaces over time, leaving physical imprints in space. Each building can be open in different contexts depending on which story you want to hear.

- Забудова: 1938

- Стиль: модернізм, функціоналізм

- Архітектори: Стефан Порембович

This article is published within the initiative Saving Objects and Stories of the Modernist Period in Ukraine. The initiative is the result of the fellowship of Myroslava Liakhovych, who runs “Lviv. Architecture of Modernism” at the Chair of the Theory of Architecture, ETH Zurich. The supervisor – Prof. Dr. Laurent Stalder, the Chair of the Theory of Architecture, ETH Zurich in collaboration with Kharkiv School of Architecture, Lviv Heritage Bureau, SKEIRON 3D Scanning. Initiative financed by ETH Zurich. Credits to the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe (Lviv, Ukraine) for providing archival materials and Sketchfab for free access to the platform.

Villa, which we choose to investigate, tells us not only about the modernist design of single-family houses but also about the turmoil of events of the Second World War, the transition from a capitalist state to soviet socialism, the contemporary story of war and dwelling rituals, placed within all these events.

The villa was built in a wealthy neighbourhood and represents an exemplary upper-class modernist single-family house in Lviv at the end of the 1930s. The project was designed by young Polish architect Stefan Poręmbowicz and implemented under the supervision of Engineer Władysław Blaim[1]. Yanina and Bruno Szymański commissioned the villa. According to findings in the archive, this couple was from the circle of Lviv’s technical intelligentsia. Bruno Szymański graduated from Vienna Technical University and was working as a Gaz technology engineer. He designed equipment and different kinds of technical installations for Gaz plants in the Lviv region and other cities of the Second Polish Republic[2]. The representative of the middle-class, often an intellectual elite, was the main purchasing power and audience for modernist dwellings. Forward-thinking architects and designers were trying to spread new esthetics and technologies through this milieu.

We don’t know much about Yanina and Bruno Szymański’s life in this villa and what happened to them during the war. According to the collected oral stories, they were forced to leave the villa and migrate to central Poland[3]. Soon after the end of the Second World War, the villa became an orphanage for children who lost their parents during the war, after which it was converted into a kindergarten.

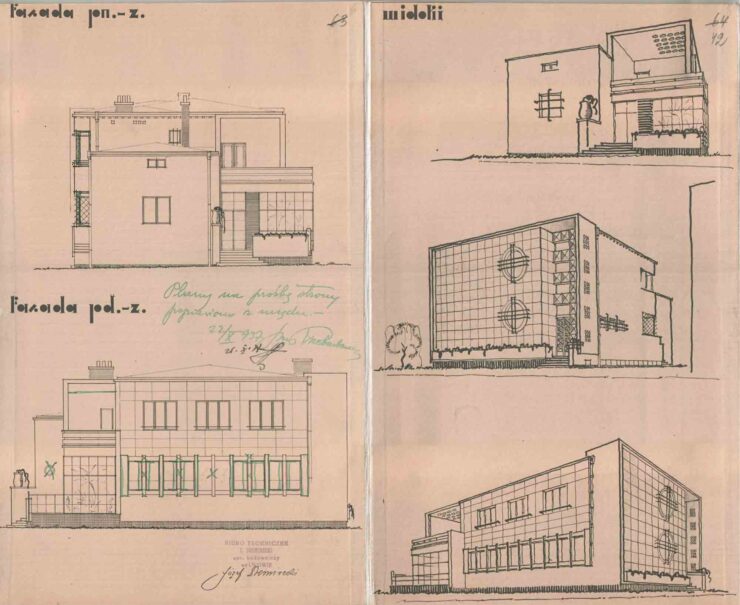

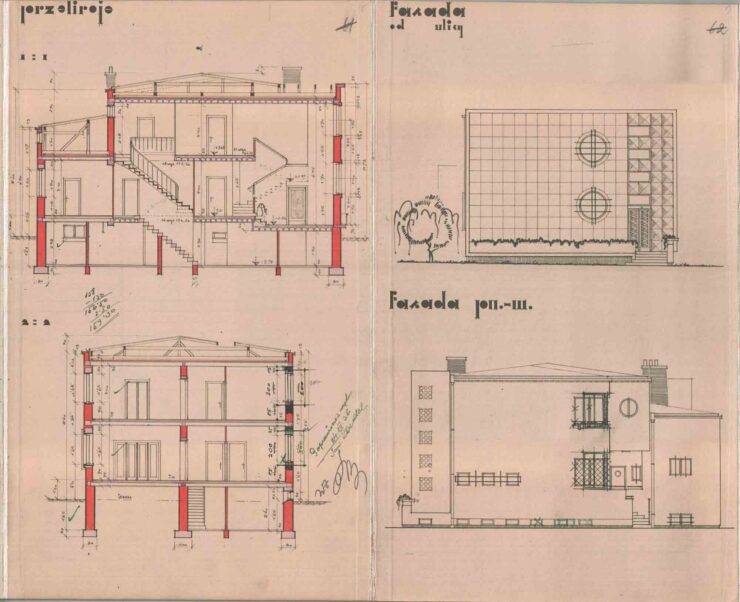

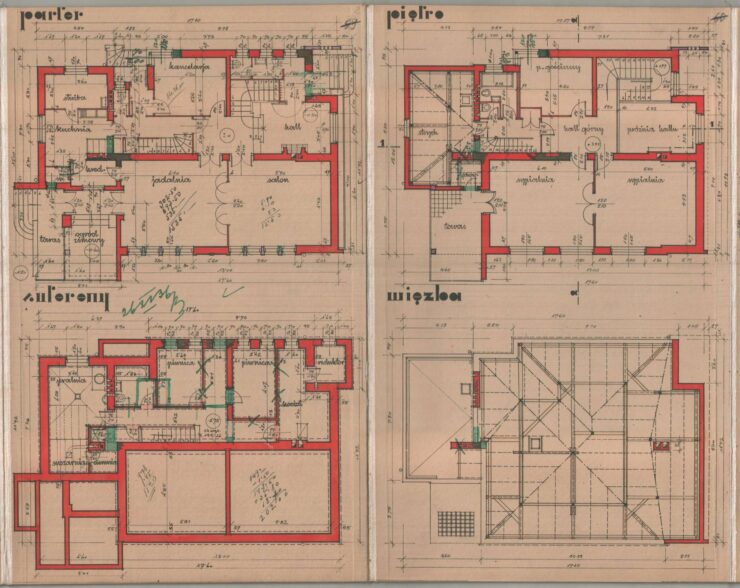

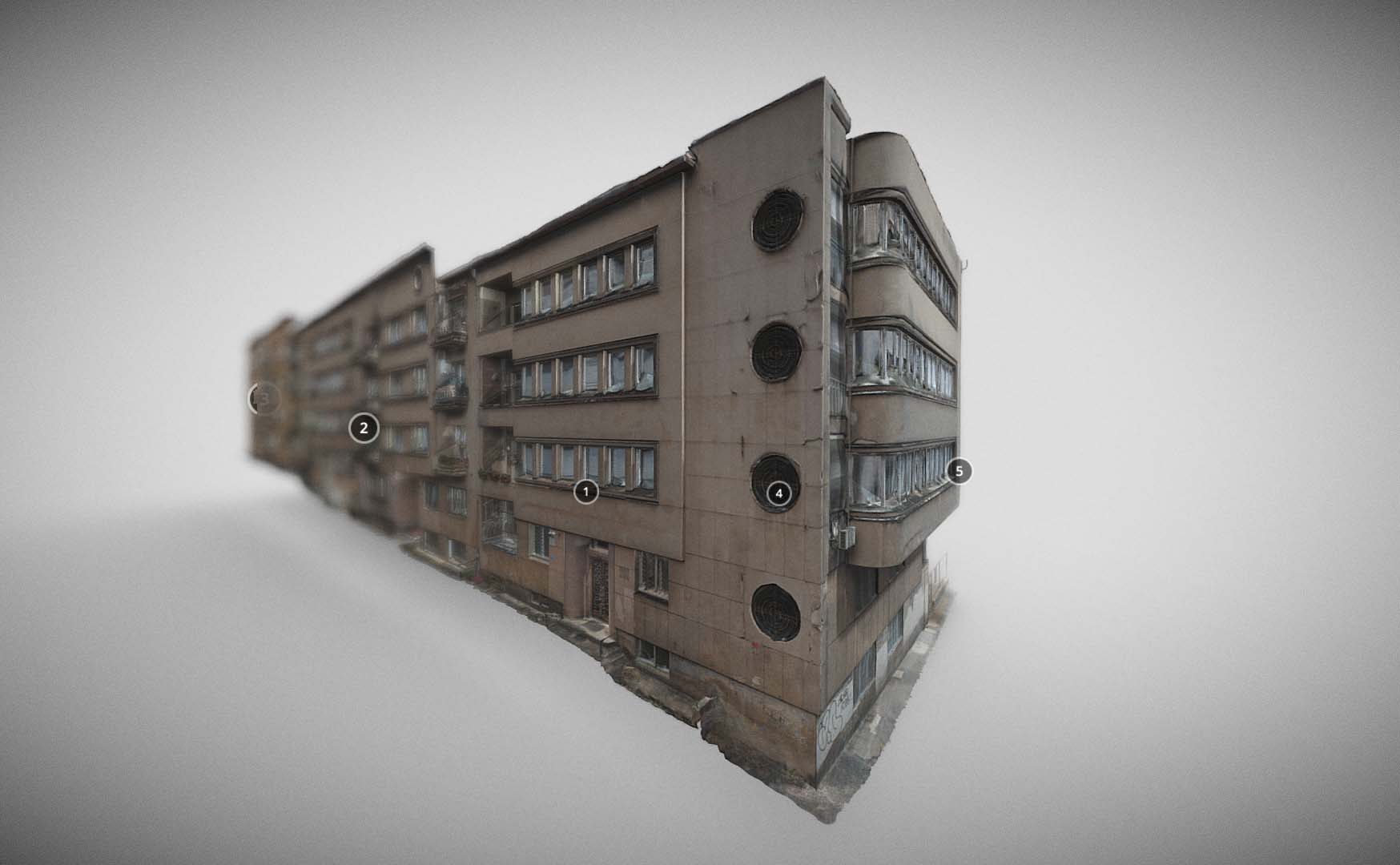

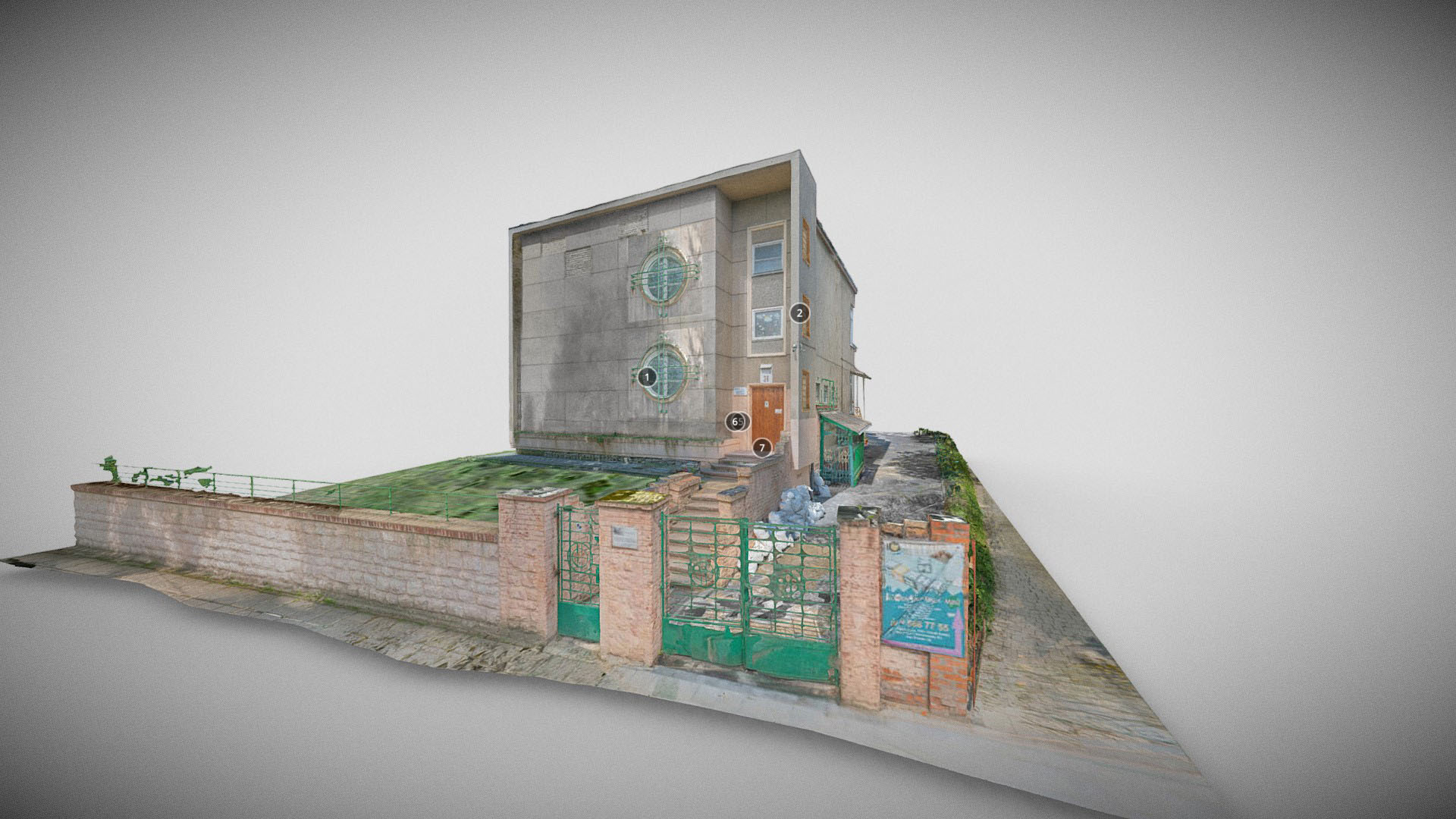

The scan of the building and the territory allows us to see the holistic plan of the architect and engineer. The villa has a rectangular form with a protrusion to the northwest side. It is made with a reinforced concrete frame, filled with brick. According to the archival materials the vault system Isteg, which was very popular among Lviv architects, was used in the construction. Engineer Jozef Dromirecki was responsible for implementing Isteg in this villa. Isteg is a system of reinforced concrete vaults with voids inside. The presence of voids made the structure lighter, and the air layer worked as insulation and reduced heat loss[4].

Taking about the façade: Almost all the elements inherent in Lviv’s functionalism of the 1930s are used in this house. Two large porthole windows with original grilles are placed on the facade of the building, which is divided into squares. These windows illuminate the central hall of the house. Thanks to the 3D model, one can see the original grilles and window frame, as well as the artificial stone framing up close.

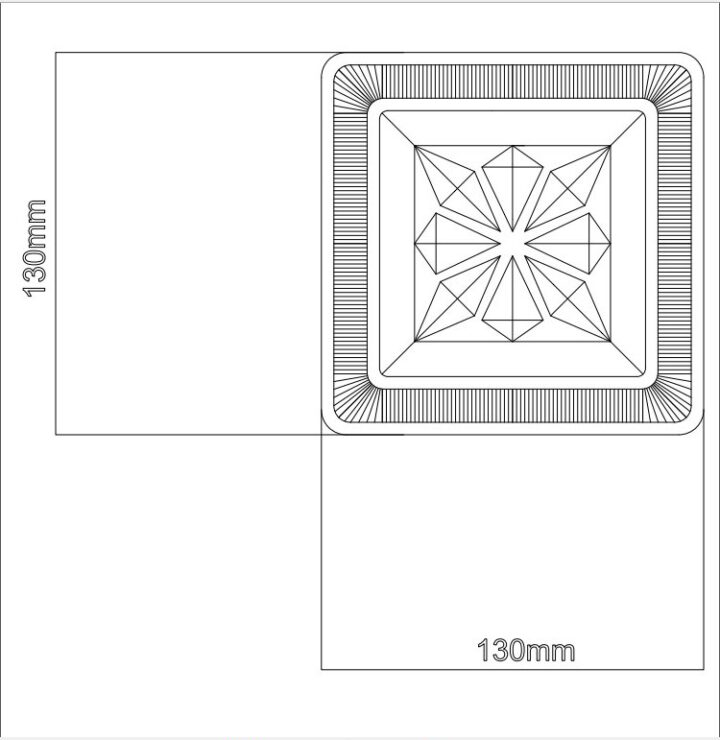

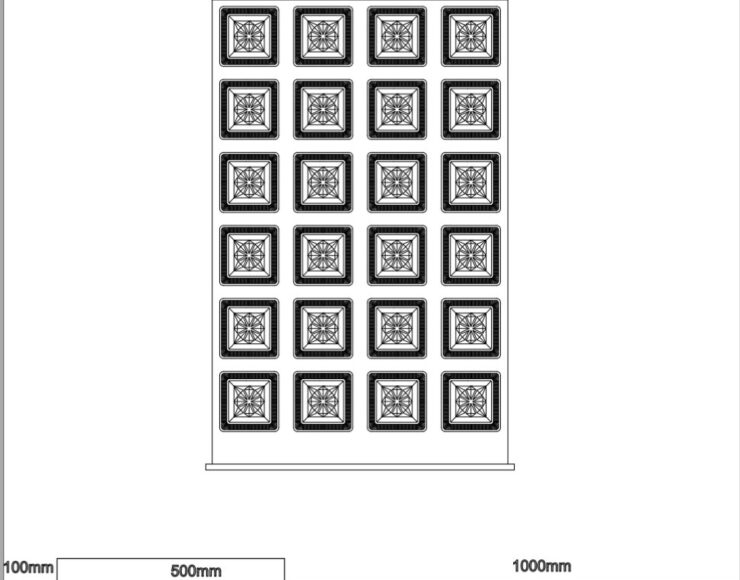

The entrance portal is very unconventionally designed; together with the entrance door and the windows illuminating the lobby, it is “sunk” into the plane of the house, and avoids direct light. The glass blocks installed in the side wall also help to diffuse the light. Having scanned a fragment of the wall with glass blocks, we can see how they are made in detail: each block has a bubble surface and a repeating rhythmic flower-shaped ornament.

According to the students’ measurements, which are depicted on the drawing, each prism is equilateral, with one side measuring 130 mm[5]. The prisms are placed in a shiny mica plaster, which is visible in the scan of the fragment. Nearby we can see the destroyed plaster, painted over with a beige color.

The villa was built together with a fence, garden and garage, which were designed by Blaim. The garage one can see in the photo.

However, the villa façade has undergone significant changes. In the archival drawings from the northwest side of the house, one can see a glass winter garden pavilion on the ground floor and a terrace with a canopy, where the glass blocks were incorporated. The glass blocks produced a tender light and protected from direct sun. Having this archival drawing we can notice the play of volumes and repetition of square and glass block motives in the front façade, greenhouse and terrace.

If we compare the existing state, seen on the 3D model and the archival drawings, we will see that the terrace and winter garden were removed and rebuilt as additional premises. In this case, the physical change of space due to political shift is evident, as the objects of the bourgeois lifestyle were transformed according to socialist kindergarten needs.

The 3D model lets us virtually enter the villa and see its current state. Villa floorplans didn’t undergo significant changes, comparing archival drawings and the current state of the villa. Even so, most of the premises changed their function. Also, very little is preserved from the interior of the villa, mostly carpentry and some decoration. We walk in using the former servant entrance, as the main one is no longer used. On the left hand, there is an office of the kindergarten director, originally it was an office of Bruno Szymański, and on the right hand, there is a kindergarten kitchen, which was the kitchen before to which the servant room was connected.

Going further through the corridor we get into the hall with the central staircase, which is illuminated by two big porthole windows. We can imagine that it had a minimalistic interior and colours, but for kindergarten, it was repainted with fairytale motives in bright colours. On the left side of the hall, there is a door which now leads to the toilet. According to floorplans, there was a small lobby, which was accessed through the central entrance to the house, beside which was a wash basin and toilet. So, first the visitor was invited to wash their hands, and only after entering the villa. This accent on hygiene rituals followed the modernist concept of that time.

If we take a closer look at the lobby, we will see alabaster panelling which was common in entrée halls of Lviv modernist houses and very colorful terrazzo-based mosaic flooring. Returning to the hall we see the central staircase which runs to the first floor. It is made with wood and bent metal handrails. Adjusting these stairs to the kids’ needs, additional metal handrails were added on the top of existing ones. One can see this in the scan.

From the hall, there are entrances to two rooms. Originally there was a salon and dining room, and today playing and sleeping rooms for kids are situated there. Examining the rooms, we found almost nothing from authentic elements, besides doors, parquet, and window sills, whose dark terrazzo structure is visible through the scratches in white colour.

From here one can go to the store room, which was originally the winter garden. The only thing that reminds us that it was a winter garden is a curved staircase, which connects the former greenhouse with the outside garden.

If we come back to the central hall and walk up the central staircase, we will enter the private part of the villa. On the first floor, the three bedrooms were located: two separate bedrooms for Yanina and Bruno Szymański and one guest room. Yanina’s bedroom was connected to the terrasse. In general, despite the division by purposes, all the rooms in the villa are connected, they flow one into another, creating one big holistic space, if one would like to open all the doors.

Nowadays all three rooms are used as children’s sleeping rooms and the fourth premise, which was created from the terrace, is a playing room. There is a staircase for the servants, directly connected with the ground floor and the cellar, where the laundry premises and boiler room used to be. One can see the staircase in the 3D model of the villa above.

Summarizing the observation of the space, we can say that this villa was built to engage in many domestic rituals of the modernist period. Rituals of hygiene, right away after entering the villa, rituals of a healthy life were promoted by having the possibility of sunbathing or gymnastics in the open air on the terrace, the ritual of retreat from the busy, loud city in the garden, which is situated in the quiet, remote neighbourhood. The terrace and the big rounded or corner windows blurred the line between outside and inside, allowing the villa dwellers to feel themselves in the nature even staying in the building. The whole concept of the villa – is to slow down the inhabitants and return them to living in nature. The house itself was built to be a living organism, having the movement of natural light, from the morning to the evening, rooms which flow one into another, circulation of air, going through big windows to the big roof terrace.

Nowadays, the villa serves as a kindergarten, and most of its premises have lost their original function, but they have been reinvented as dwelling spaces for kids. In some way, the building saved its recreational function, offering quiet spaces for learning and sleeping and closeness to nature. However, this peaceful being nowadays is interrupted by air alarms and the danger of russian attacks on the city, which created a new ritual for the former villa space – the ritual of hiding from war. This ritual was imprinted in the space, as the premises of former laundry rooms in the caller were converted into the bomb shelter. Today, this villa is a hideaway from the big city, but it also literally serves as a shelter from a harsh contemporary reality for the youngest generation.

Text, photos: Myroslava Liakhovych

Scanning and modelling: made by Maria Murai, Maria Haiboniuk, Illia Oizer, Sofia Holz (Kharkiv School of Architecture). Fedir Ilkiv, Eugenii Kalchuk, Maksym Oholiev, Yana Kostiusheva, (Skeiron).

Sources and literature:

[1] State Archive of Lviv Oblast 2/1/2199

[2] Gaz i woda, nr 8, 1935, Kraków; Wieleżyński L., Wspólna praca-wspólny plon. Życie i dzieło mądrego człowieka, Kraków 1998 (2. wyd.)

[3] N. B., personal communication, April 13, 2021

[4] Przegląd budowalny, nr 20, 1930, Warszawa

[5] Drawing made by Kharkiv school of Architecture.