Dwelling archaeology: Lviv modernism through interior objects

When it comes to preserving architecture, the focus is often on the facades and entrance halls that fall under general city laws regarding heritage. Flat interiors often are not protected since they are private spaces, and their preservation relies on the goodwill of their owners.

- Забудова: 1938

- Стиль: функціоналізм

- Архітектори: Генрик Зандіг

This article is published within the initiative Saving Objects and Stories of the Modernist Period in Ukraine. The initiative is the result of the fellowship of Myroslava Liakhovych, who runs “Lviv. Architecture of Modernism” at the Chair of the Theory of Architecture, ETH Zurich. The supervisor – Prof. Dr. Laurent Stalder, the Chair of the Theory of Architecture, ETH Zurich in collaboration with Kharkiv School of Architecture, Lviv Heritage Bureau, SKEIRON 3D Scanning. Initiative financed by ETH Zurich. Credits to the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe (Lviv, Ukraine) for providing archival materials and Sketchfab for free access to the platform.

In Lviv, the interiors and material culture hold a unique value as they contain a wealth of information about the lost modernist era. After the Second World War, Lviv lost over 90% of its population, and new residents took over the material culture of strangers[1]. The furniture, appliances, and fittings of the interiors hold unique information about the original inhabitants and their way of life that one would never find in archives.

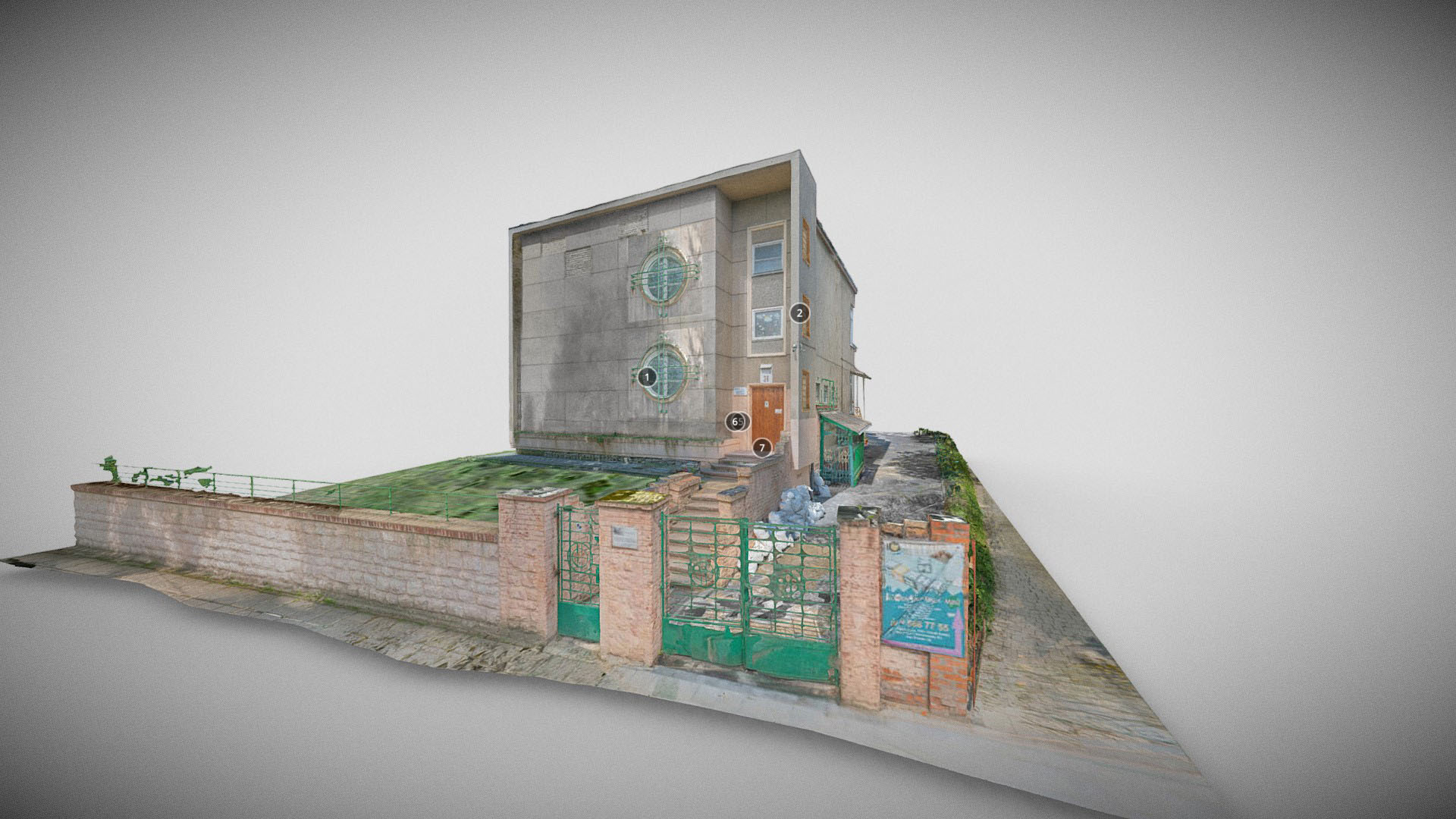

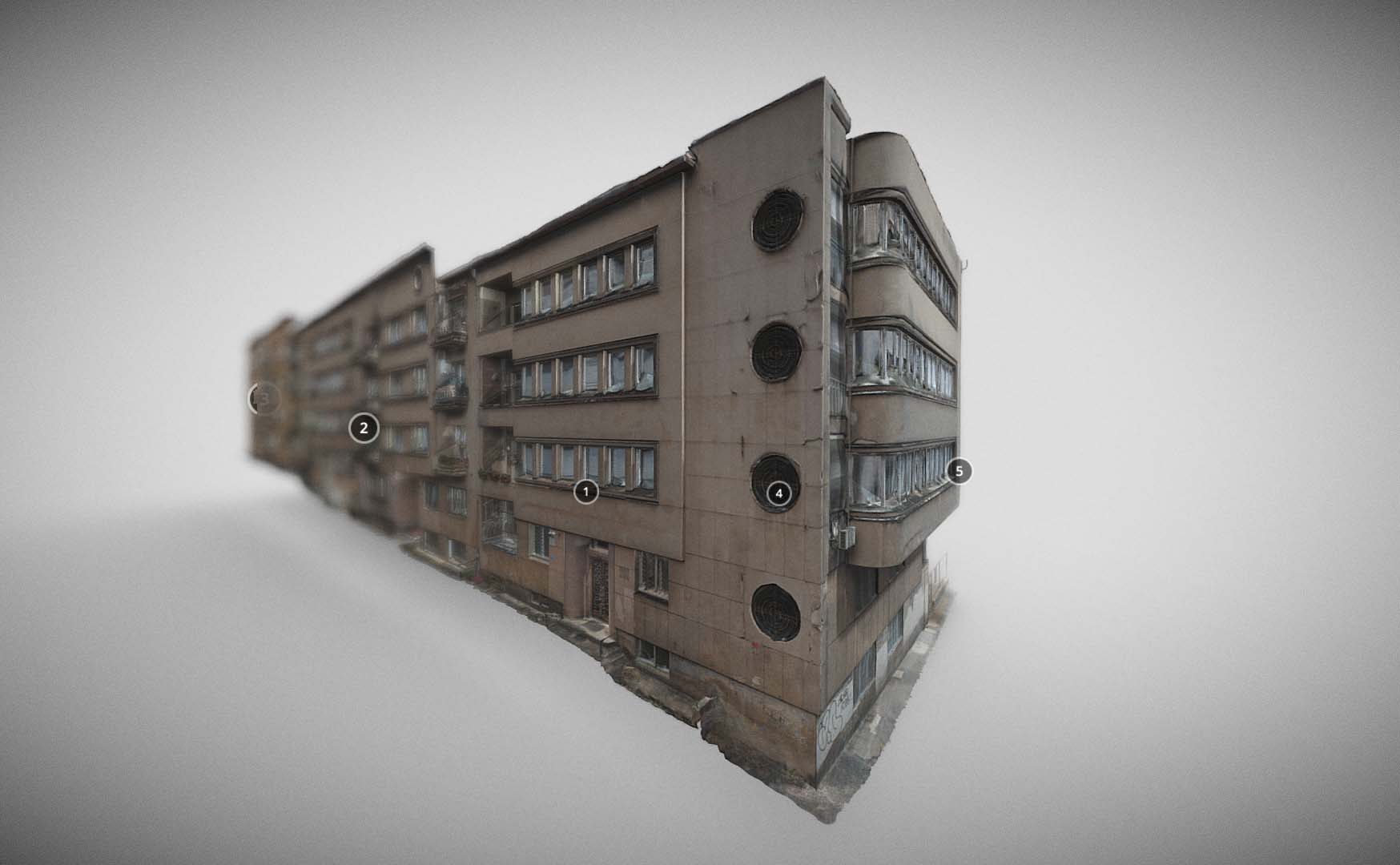

Numerous historic flats in Lviv have regrettably been lost due to residents being detached from their tangible surroundings. Many valuable items, appliances, and fittings were often discarded without recognising their worth. It is uncommon to find a well-preserved interior with amenable owners. However, we were fortunate enough to receive authorization to scan and present an exceptional flat from the 1930s, which includes original interior elements, furniture, and appliances. Additionally, we have scanned the whole housing complex at 47-59 Doroshenka St. The entire 3D model and research article are currently available on this website.

This flat is in the middle-class housing complex built in 1938, primarily for wealthy Jewish families. The house №49, where the flat is located, was built for rent and was owned by Karolina and Maks Spitsmann and designed by architect Henryk Zandig[2]. They all were killed during the Holocaust. We know nothing about the original tenants of the flat. Probably, they were also killed or deported. After the war, the apartment was given to the family from the Soviet establishment[3]. This is not a rare case; in the Soviet Union, despite a declared socialism, some people were more privileged than others. In Lviv, most luxury housing was owned by party functionaries or KGB workers[4]. The family who kept the apartment in an almost authentic state chose to remain anonymous. Now, the apartment is rented out.

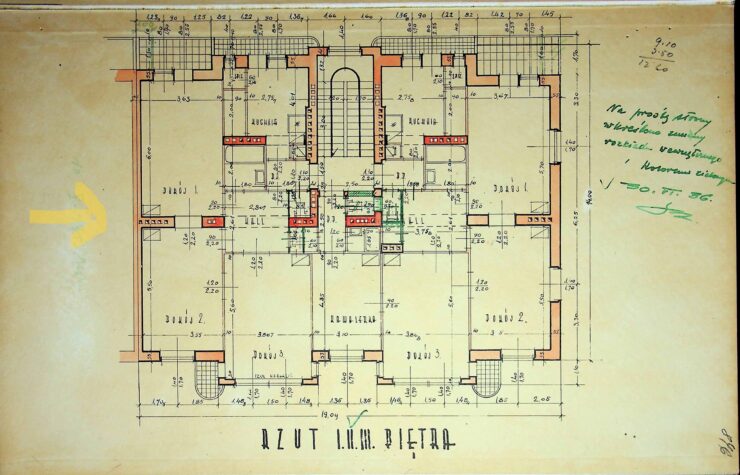

You can walk through the apartment using a 3d model and read about concrete objects in the annotations. By leveraging 3D scanning technology, we can virtually explore and reconstruct living spaces, piecing together the intricacies of the world from almost a century ago. If we compare 3D model with the drawings[5], we will see that the layout of the apartment has not changed at all.

We start our journey in the corridor, where one can leave shoes in the small build-in closet in the lower right corner. Built-in furniture was one of the main features of modernist design, concerned with hygiene and order: things should be hidden to liberate space in the apartment, and dust and dirt should be reduced to a minimum[6].

As we make our way towards the right, we enter the kitchen. The room has undergone significant changes, with only a table and several chairs remaining from the original furniture. However, some furniture, appliances and the original layout have been preserved. On the left one can see a sink, typical of the 1930s, is divided into two sections – one for washing and the other for drying dishes.

Like the typical chair Mundus, which was a part of Thonet Brend, about which stamp situated under the chair sit, says. Furniture from Vienna was widely used in Lviv, maybe because Vienna remained, at that time, a cultural landmark for the Lviv people.

Among the appliances in the kitchen, one can see the ESWU boiler, which is responsible for heating the entire flat, which is still in use, and the water thermometer. Both were made in Poland and ordered from the city of Łódź.

This kitchen has a niche with a sleeping couch for the servant (which one can see in the general model and photos above), a common feature in modern apartments in Lviv and other European cities. Despite the availability of modern appliances and aesthetics, the lifestyle of bourgeois people remained unchanged. It’s possible that a servant of a Soviet family also resided there.

When we turn left in the corridor, we come across a so-called blind hall that branches into several rooms. There’s a coat rack with a walnut veneer and a built-in closet. A small radiator in one of the corners catches our eye with its temperature regulator, which has the installer’s name, Engineer Harszan, Lwów, inscribed on it.One can see a device in the photograph. The radiators in the entire flat, as indicated by the stamps, were manufactured by plant Strachowice from central Poland.

Upon examination of the hallway, it is apparent that each apartment door has been carefully preserved, complete with glazing that allows natural light to illuminate the rooms.

The living room, accessible through the doors with large glazing, boasts its original interior.

The furniture in the room, including an Art Deco table and cupboards with walnut veneers, indicates a preference for this type of furniture among the local bourgeois rather than the more lightweight metal tubular furniture. Due to previous research, such furniture was the most common in Lviv flats[7]. The furniture bears no discernible stamps; a small, local workshop probably crafted it.

Deep in the cupboard is laying another trace of 30-es – a tray broken in pieces; it consists of ceramic framed with metal. Beautiful birds on a tree in Art Deco style are depicted on the tray. The stamp on it says that it was produced in Czechoslovakia; of course, we can not say for sure if the original inhabitants left this tray or if a new soviet one got it somewhere in Lviv.

The other finding in the cupboard is an alabaster napkin holder and a small fragment of lost esthetic tableware. Alabaster was one of the most popular stones in the 1920es and 1930es in Lviv. It looked like marble and was less expensive; the source of alabaster was in the region. This stone was used in the decoration of interiors, lamps and other table objects were produced from it. In Lviv the world’s fashion for marble was glocalized to the fashion of alabaster.

On a smaller cupboard beside the wall, one can see a desk lamp designed by a famous Dutch architect and participant of the De Stijl movement, Jacobus Johannes Pieter Oud. This lamp Jacobus was broadly produced in Germany in the 1930s. We can assume that interwar occupants of the flat ordered it from Germany as this country was a second important influencer of the modernist style of life in Lviv in the 1920es and 1930es.

In this room and around the whole flat, it is complicated to see the glazing of windows, as the laser scanner works quite badly with the recording of glass and shining surfaces. In this case, photo documentation is more helpful: in the photographs, one can see the double layers of authentic glass. Besides it, the traces of anti-aircraft shutters. Nowadays, the only protection against broken glass in case of a bomb attack is white adhesive tape in each window.

The living room has a glazed door to cabinet: when doors are open, the living room and cabinet appear as one space, which was quite common for 1930s design. In the cabinet, which is now the bedroom of one of the tenants, we have a combination of an Art Deco sofa, a historicism closet and a soviet table and bookshelf. Some furniture pieces changed their purposes, like this sofa for reading, which is now used for sleeping ( the room you can see withing the general model of the flat).

In between the cabinet and the bedroom should be a door, which is blocked today, but preserved door frames are still there. Probably before the Second World War, this flat was rented by one person or a couple, which had no need to divide the space, but later, when bigger family got the apartment, they needed more privacy and adjusted these to rooms differently. In the bedroom today, a room of another tenant. Just the radiator beside the window left from the modernist interior, other things a mixture of Soviet and historicism design.

Investigation of this flat is not finished. We found things and imprints which provide more questions than answers. Nevertheless, for now, we have an approximate imagination of what the dwelling in the late 1903s in Lviv looked like. This life was a bit different from this depicted in Bauhouse propaganda journals, without light furniture but with an alcove for servants. However, this flat was centred on functionality with its central heating, built-in furniture and rooms which could be connected or separated in different ways, with appliances which was at least partly a liberation of household work for servants.

Speaking about appliances, we see that none of the items we found in the flat are from Lviv. During the interwar period, Lviv was not a big industrial centre, without any heavy industry where boilers or other devices were produced. As earlier investigation confirms, most of the heaters, radiators, and stoves were produced in central or western Poland and exported to Lviv; also, many appliances were exported from Germany and the Netherlands. Sanitary ware and other goods, especially ceramic, were Czecho-Slovak. As we can see here from the Mundus-Thoneth brand, lots of furniture was coming from Vienna. Nevertheless, one can also encounter Lviv art deco furniture, but it is hard to assert for sure, as most of these pieces have no stamps, like the cupboards in the living room.

As we see here, objects can induce us to ask questions, force us to investigate them, and speak about them. In this way, objects and materiality obtain agency. When objects move through space and time, they start to have their own social life and spread different meanings or stories, which can describe a style of life, economic circumstances, or historical events[8].

Using archaeological approaches in the investigation of materiality in this flat, analysing stamps, and searching the origins of materials and objects, we can assume that the interwar inhabitants of this flat were with one leg got into modernity, using modern appliances and living within the modernist planning and design esthetics, and the other – staying with servants and heavy cupboards. These people lived in fear of the war, ordering anti-aircraft shutters for their windows in 1938. The current residents have air alarms and shelling from time to time, but they hope that this house and flat will survive this war, too, and they will not have to flee.

Text, photos: Myroslava Liakhovych

Editing: Pamela Johnston

Scanning and modelling: made by Oleksandr Holovashkin, Paulina Marchenko,Georgij Maksymenko, Maria Murai, Maria Haiboniuk, Oleksandr Podolskyj, Anastasia Aniskina, Sofia Holz (Kharkiv School of Architecture). Fedir Ilkiv, Eugenii Kalchuk, Maksym Oholiev, Yana Kostiusheva, (Skeiron).

Sources and literature:

- [1] Jan Fellerer and Robert Pyrah (eds.), Lviv and Wrocław, Cities in Parallel? Myth, Memory and Migration, c. 1890–Present

(Budapest: Central European University Press, 2020). - [2] State Archive of Lviv Oblast 2/2/3764

- [3] V. P., personal communication, May 13, 2023

- [4] Henryk Żaliński, Kazimierz Karolczak. Lwów: miasto, społeczeństwo, kultura : studia z dziejów Lwowa. Naukowe WSP, 1996

- [5] State Archive of Lviv Oblast 2/1/3764

- [6] Martin Kohlrausch, Brokers of Modernity: East Central Europe and the Rise of Modernist Architects, 1910–1950 (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2019)

- [7] Myroslava Liakhovych, “Hallet House: A Building that Saw the Deaths of its Inhabitants, Hungarian Communist leaders and SS Officers”, Lviv – Architecture of Modernism, 6 May 2020, https://modernism.lviv-online.com/budynok-halletiv-ar-dekovepomeshkannya-scho-bachylo-smert-svojih-meshkantsiv-ofitseriv-ss-ta-uhorskyh-komunistychnyh-lideriv/;

- [8] Arjun Appadurai, The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, Cambridge University Press:1988