A modernist dwelling for all: social housing at Hrekova Street

During the modernist era and following the First World War, Europe faced a housing shortage, making the slogan “Fast housing accessible for all” an appealing solution.

- Забудова: 1929 - 1930

- Стиль: модернізм

- Архітектори: Збігнєв Жипецький

This article is published within the initiative Saving Objects and Stories of the Modernist Period in Ukraine. The initiative is the result of the fellowship of Myroslava Liakhovych, who runs “Lviv. Architecture of Modernism” at the Chair of the Theory of Architecture, ETH Zurich. The supervisor – Prof. Dr. Laurent Stalder, the Chair of the Theory of Architecture, ETH Zurich in collaboration with Kharkiv School of Architecture, Lviv Heritage Bureau, SKEIRON 3D Scanning. Initiative financed by ETH Zurich. Credits to the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe (Lviv, Ukraine) for providing archival materials and Sketchfab for free access to the platform.

The aim was to give the masses access to “new living,” incorporating modern lifestyles, innovative materials, objects, and aesthetics.[1] However, the reality was that the consumers of these modern homes were mainly better situated, the high cost of the appliances and materials making them unaffordable for most people.[2] Social housing projects were few and far between and were often subsidised by the state or large companies. In Poland, housing projects for the masses were mainly developed in the Central Industrial District, one of the country’s most significant economic projects of the time and consuming around 60% of all investment funds. This did not include Lviv, a city on the eastern Polish border, which lay outside the Central Industrial District and failed to attract significant investments from big industries or the state.[3] As a result, most housing projects in Lviv were commissioned by private owners for commercial use and were exclusively reserved for upper- and middle-class citizens.

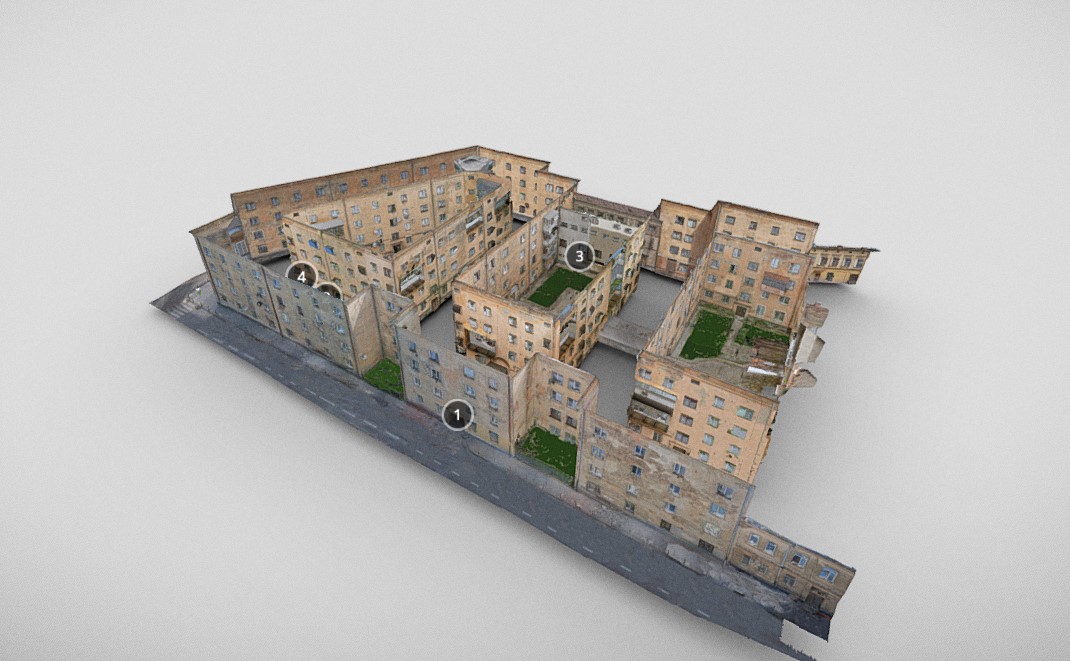

The outcome is that, historically, Lviv has very few working-class municipal housing blocks from the era. In order to digitally preserve this scarce and precious heritage, we have focused on a specific block at 8 Hrekova Street. This building is a testament to successful social housing initiatives undertaken by the municipal authorities in the industrial region of Pidzamche. The block was built near a railway and a square that once hosted a bustling cattle market, while the western side is flanked by barracks dating back to the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The majority of residents were employed in nearby factories and workshops.[4]

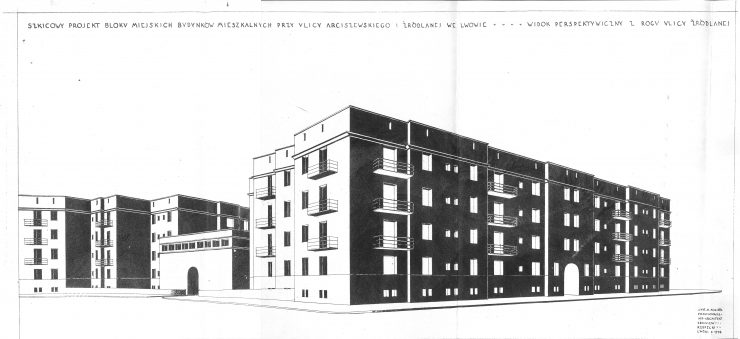

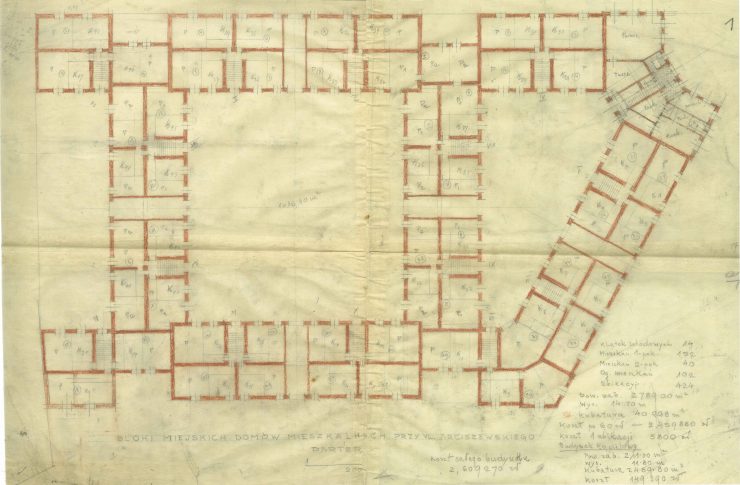

Architect Zbigniew Rzepecki created two different designs for the building’s façades. The first design featured a more dynamic layout, providing almost every flat with individual layouts and balconies, as shown in the drawing.[5] However, reducing the costs of the project was a priority, and a simplified version was ultimately chosen for construction. As a result, many balconies were eliminated, and the floor plan was simplified, with construction beginning in 1928.

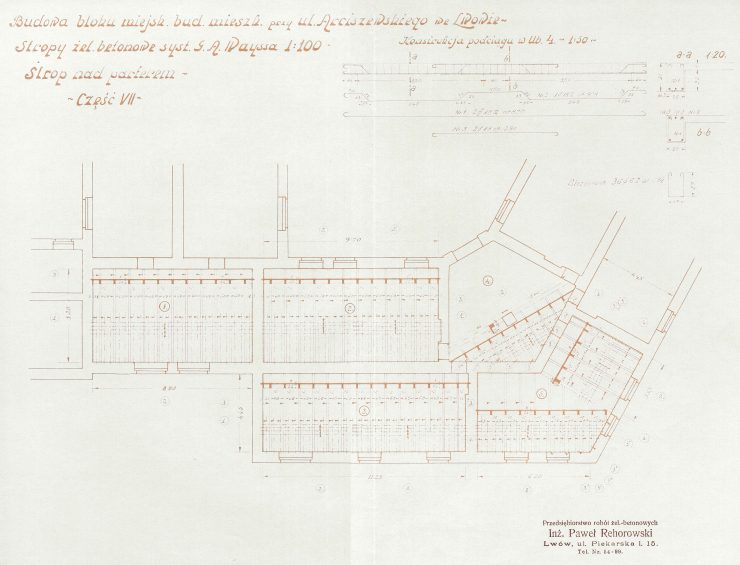

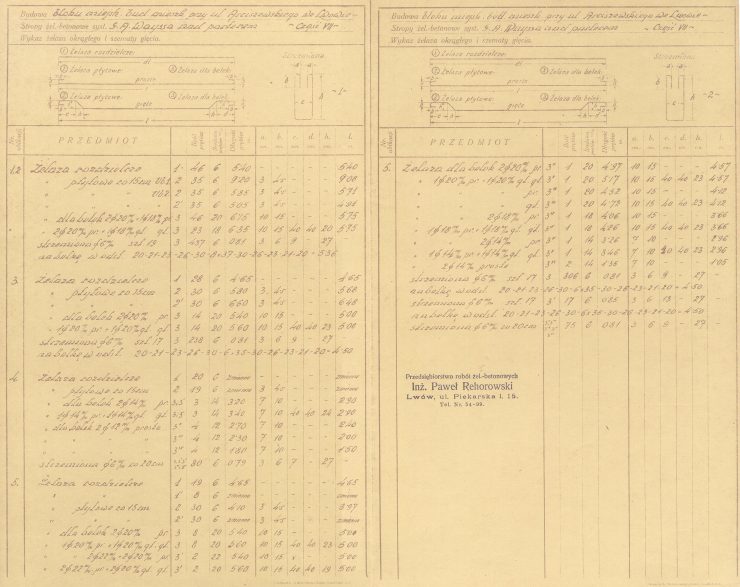

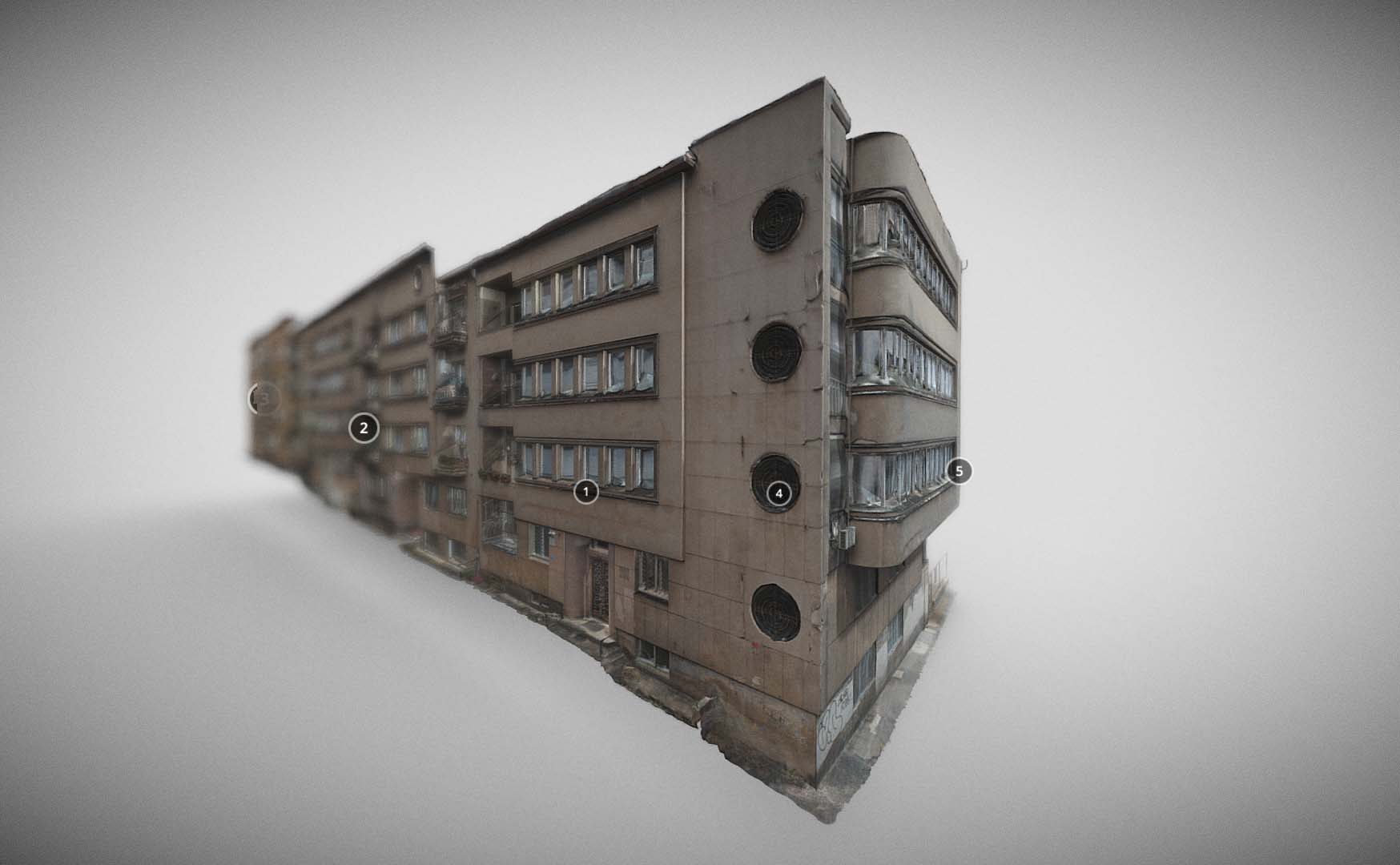

The housing project was completed efficiently according to contemporary mass-construction standards. The foundations were poured in reinforced concrete, and reinforced concrete elements were installed by the local company Paweł Rehorowski.[6] An analysis of the deteriorating plaster of the façade sheds new light on the building’s construction, with scans indicating that the frame was infilled with brick.

The building has two enclosed courtyards. 3D scanning has shown how the house connects to the neighboring buildings to create a third enclosed courtyard, even though it appears open in the original drawing. Looking at the 3D model from a bird’s-eye view, we can simultaneously evaluate the layout and location.

However, two portions of building defied modern regulations and lack sufficient lighting, as they are located inside the courtyards. The staircases within the building are also dark and poorly ventilated, indicating a lack of consideration for modern standards. Interestingly, the central part of the building is the public baths, positioned there for hygienic purposes, and although it is hard to distinguish from the current state of the building, the archival photographs reveal its central location.

The project is completely lacking in decoration besides four arches, which connect the courtyards and create an open corner with four rounded balconies.

The entrance interiors and staircase balustrades are simple and streamlined.

The flooring consists of light-yellow asphalt tiling, and the balustrade is comprised of concrete, metal grids, and wooden bannisters.

The shape of the staircase railing mirrors that of the balcony railings. On the east side-corner of the building, one staircase stands out from the rest; its pentagonal configuration invites in light and air, as demonstrated in the models.

The buildings consisted of one-room apartments with kitchens and toilets but no bathrooms, meaning that the communal baths was vital to the project. However, this space proved to be insufficient for the needs of working-class families.

This issue was addressed in the 1960s and 1970s by altering the building’s architecture. New residents began to glaze and cover their balconies without authorization to increase their living space. The model shows that only one balcony has remained in its original form.

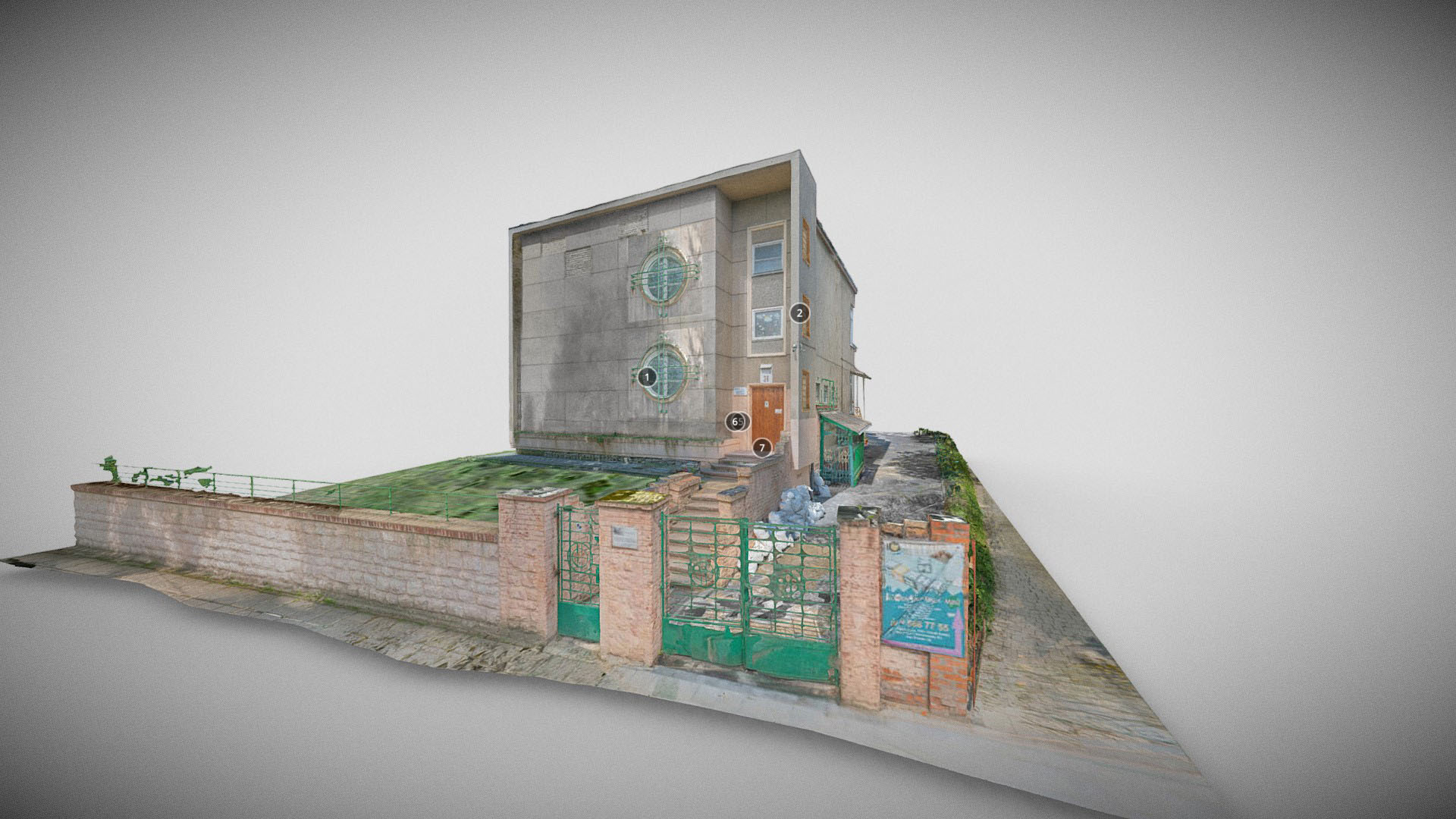

The model and photos depict the poor state of preservation of the building. The plaster on the façade is deteriorating and the original wooden windows and doors have been replaced with plastic ones. The communal baths building has undergone significant changes. Residents were offered by the city authorities built bathrooms inside their flats already in 1970s. The baths building has been privatized after the collapse of the Soviet Union and converted into a hotel, with the façade changed from a minimalist to a pseudo-vernacular style. Overall, it is difficult to recognize how the original building once looked.

Historically, this particular building was seen as a valuable investment by the municipal authorities as a social landmark. In order to make it affordable, cheaper materials and some outdated architectural methods were utilized. Despite this, the building still had a modern feel due to its efficient construction techniques, simple exterior design, and accessibility to lower-income tenants. The project is interesting not just as an embodiment of modernist ideas but also in the way that changing political systems and shifts from communal to private values have left significant imprints on it.

Text, photos: Myroslava Liakhovych

Editing: Pamela Johnston

Scanning and modelling: Eugeniy Kovalchuk, Sofia Holts, Paulina Marchenko, Anastasia Aniskina (Kharkiv School of Architecture), Georgiy Maximenko, Maksym Oholiev, Yana Kostiusheva (Skeiron).

Sources and literature:

- [1] Hilde Heynen, Architecture and Modernity: A Critique (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999).

- [2] Robin Schuldenfrei, Luxury and Modernism: Architecture and the Object in Germany, 1900–1933 (New York: Princeton University Press, 2018), 19–24.

- [3] Bohdan Cherkes and Andrzej Szczerski, Lwów: Miasto, Architektura, Modernizm (Wrocław: Muzeum Architektury we Wrocławiu, 2016).

- [4] Yulia Bohdanova, “Architecture of the Interwar Period (1919–1939),” in Volodymyr Biryulev (ed.), Architecture of Lviv: Time and Styles, XIII–ХХІ Century (Lviv: Center of Europe, 2008).

- [5] State Archive of Lviv Oblast 2/2/5546.

- [6] State Archive of Lviv Oblast (see note 5).