Sprecher’s “skyscraper”: flirt with virtual reality, consumerism and vision of a future

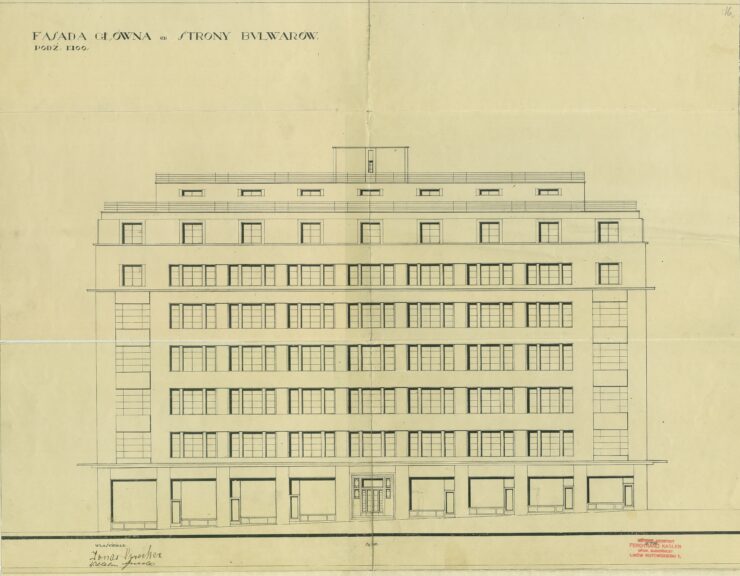

Minimalist facade, elongated horizontal windows, glazed risalits, flat roof, and seven stories — Sprecher’s “skyscraper” shocked city inhabitants in 1929. For some people, this building was a place of inspiration, while for others, it was a reason to complain. For example, a local journalist wrote in the newspaper “Nowiny Poranne” (“The Morning News”) that this large building spoiled the boulevard’s silhouette[1].

- Забудова: 1929

- Стиль: ар деко, модернізм, функціоналізм

- Архітектори: Фердинанд Каслер

This article is published within the initiative Saving Objects and Stories of the Modernist Period in Ukraine. The initiative is the result of the fellowship of Myroslava Liakhovych, who runs “Lviv. Architecture of Modernism” at the Chair of the Theory of Architecture, ETH Zurich. The supervisor – Prof. Dr. Laurent Stalder, the Chair of the Theory of Architecture, ETH Zurich in collaboration with Kharkiv School of Architecture, Lviv Heritage Bureau, SKEIRON 3D Scanning. Initiative financed by ETH Zurich. Credits to the Center for Urban History of East Central Europe (Lviv, Ukraine) for providing archival materials and Sketchfab for free access to the platform.

This architectural project was commissioned by manufacturer and financier Jonasz Sprecher and designed by the famous architect Ferdynand Kassler[2]. This house embodied all the glory of commercial modernist architecture. It was erected on one of the biggest central city streets Akademiczna (today’s Shevchenka avenue). The simple, plain façade was a perfect surface for neon advertisements. Huge glass vitrines on the ground floor, accentuated by horizontal lighting incorporated into the building’s canopy, invited customers even after dark. The building seemed to float between heaven and earth, plastered with a layer of shiny, bright mica that contrasted with the ground floor’s heavy travertine panelling.

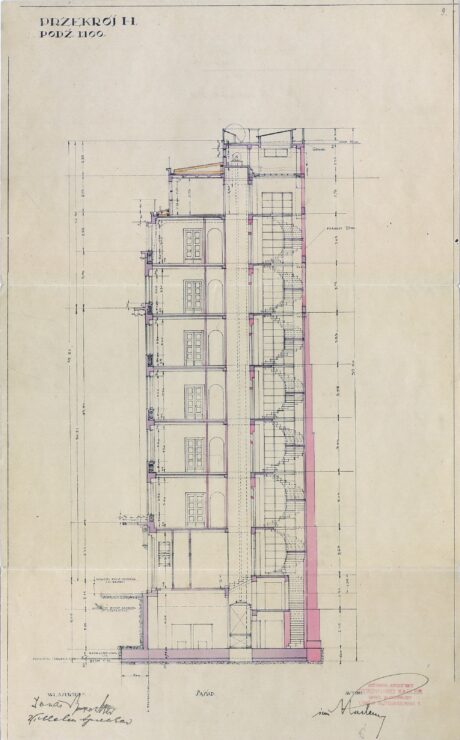

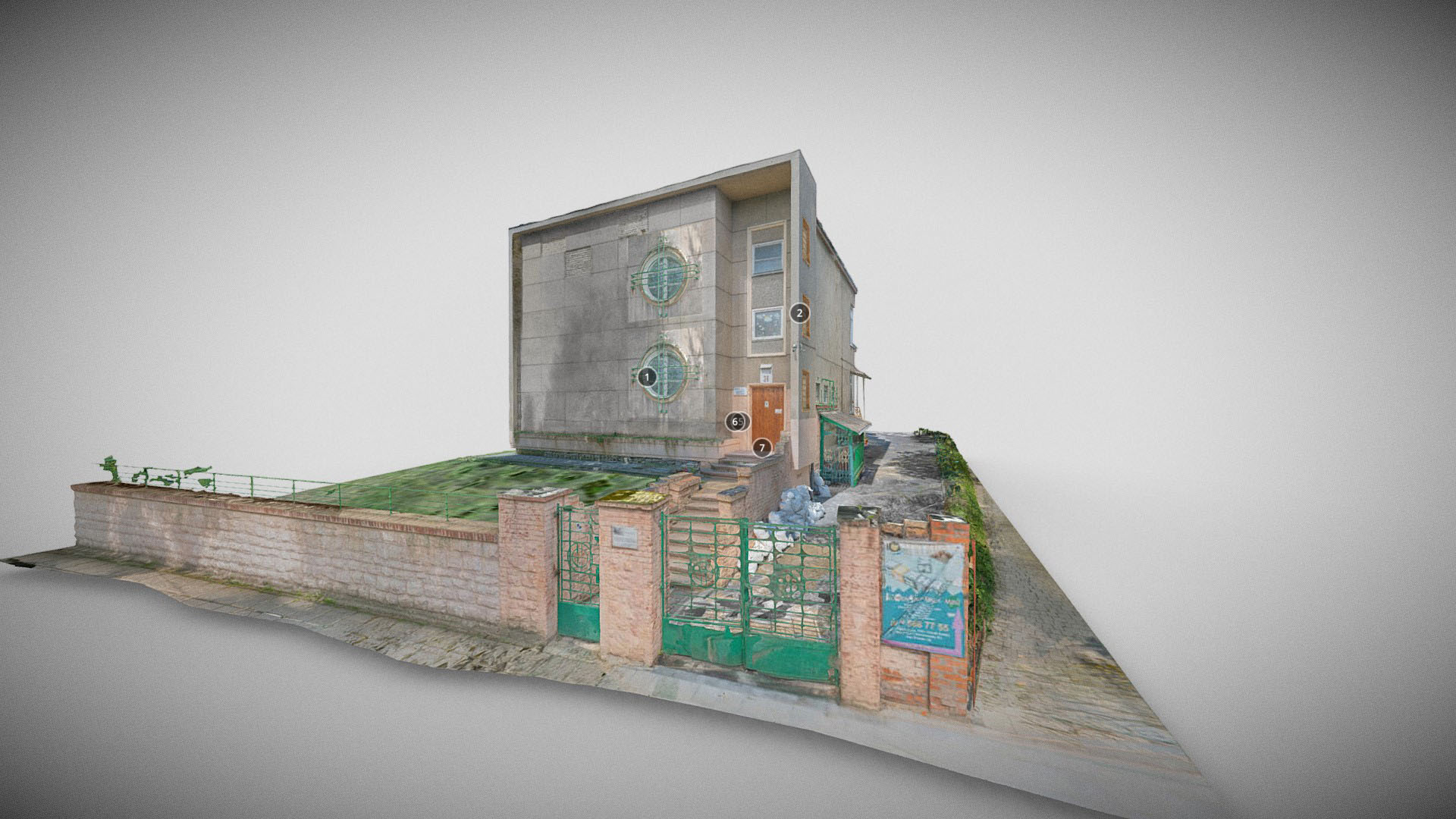

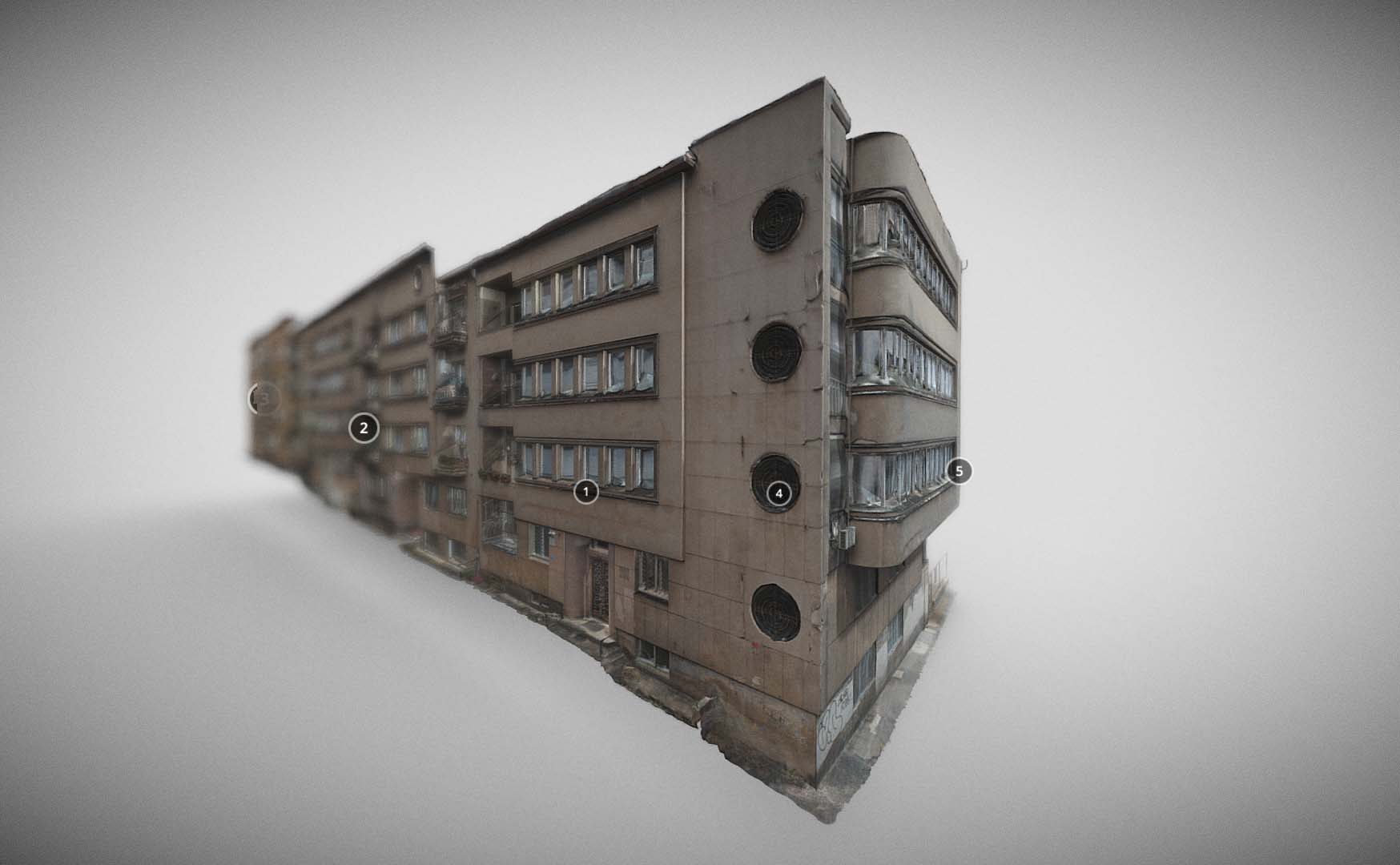

The building has an elongated rectangular form, as evident in the comparison between the archival floor plan and the 3D model. The north part of the building is adjoined to the older urban fabric. According to archival materials, the building construction was based on a reinforced concrete frame with inner brick walls[3].

Reinforced concrete slabs between floors have a peculiar wave-like form, where the voids are filled with air, serving as an additional isolation tool. The construction of the house was shrouded in legends. Some of them were saying that Sprecher’s “skyscraper” was built on top of the river Poltva. However, the architect Ferdynand Kassler refutes this information in an interview in the local newspaper “Chwila”. The building is only partly positioned on the old riverbed, where the soil is not stable enough, said the architect[4]. That’s why the ground beneath the foundations was strengthened with a 105 cm thick reinforced concrete slab.

Turning now to the facade, it definitely lacks decoration, but the forms and size of the windows, glazed risalites, and shiny mica plaster create a play of volumes and light. Not plaster mouldings, as on historicist buildings, but rational usage of light, shadows, transparency, and streamlined forms, which embodied the velocity of that time, were the main beauties of this house.

The whole facade consists of connected horizontal windows. Elongated large vitrines on the ground floor were positioned at the level of street traffic to be accessible not only for passersby, but also for car drivers. In this case, the building not only reflected the aesthetics of traffic, but also participated in it.

Talking about the shop windows, they sat between travertine panelling. In the past, frames were made of chrome, but today they are replaced with plastic. This cheap contemporary material diminishes the overall concept of shiny, reflective surfaces linked to 1930s consumerist aesthetics. If we examine the model from all angles, we see that the shop windows cover the entire facade of the ground floor. The shop window was a modern invention from the 19th century, but it reached its peak of development and significance during the 1920s and 30s. As Sprecher’s “skyscraper” was meant to be the financial and trade hub of Lviv, the presence of high-end shops was essential. Even then, modernist architecture was criticised as being designed mainly to showcase shop windows and neon signs, which will be further discussed. Therefore, the main feature of the building was a commercial space intended to attract customers inside, as Janet Ward notes in her book “Weimar Surfaces”[5]. Passers-by were drawn in by the vitrines, which were not only made to sell goods but also to convey fashion and new ways of life. The transparency of the big window, for the first time in spatial design history, enabled people to be both inside and outside simultaneously. The large vitrine also created an illusion for people who were outside, that they were already within the shop or immersed in this displayed imaginary life, even if they could never afford any of it[6].

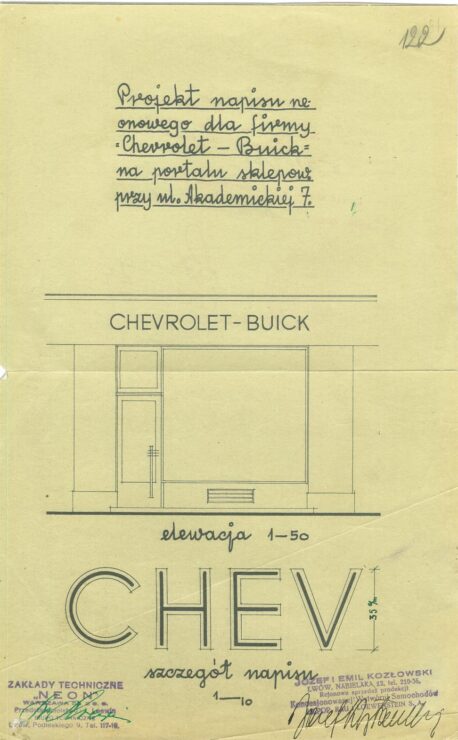

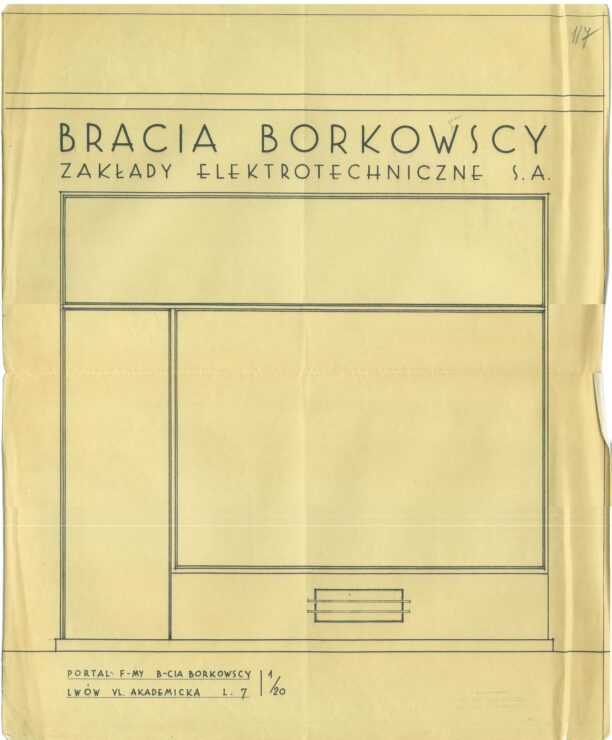

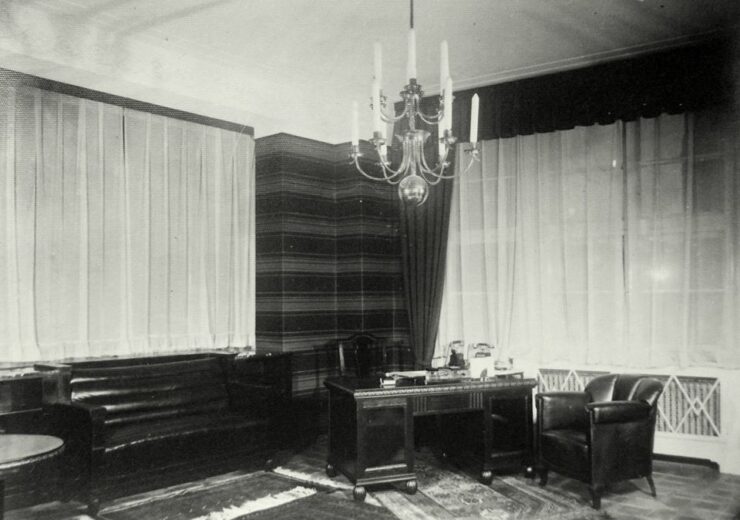

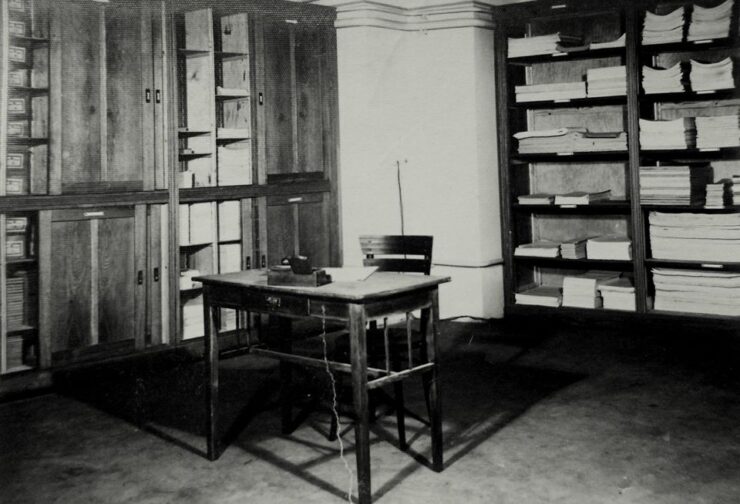

Hence, according to archival materials, there was a shop called Record Cravats that sold expensive ties. There was also “Bracia Borkowscy” Shop, the most popular brand in Poland, offering a variety of lamps and electric lighting, as well as “The Chevrolet Buick” Car Salon. Besides shops, there was the Poznan branch of Bank Cukrownictwa S.A. (Sugar Industry Bank) and the office of Warsaw Insurance Company “Vita-Kotwica”[7]. One can see how the interiors of the bank, some offices and fragment of staircase looked during those times in preserved archival photos. There were chrome bannisters on the staircase and doors, expensive wooden bureau furniture, floors covered with linoleum, and suspended ceilings with recessed lighting. Since 1999, the space housing the McDonald’s restaurant has undergone renovation, and nothing original remains in the interior.

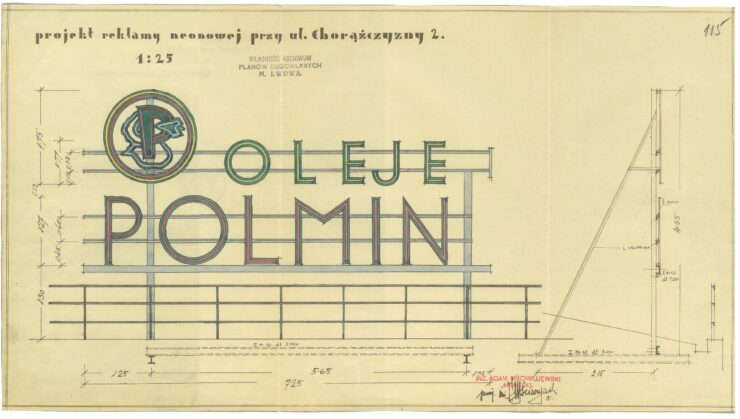

Each of these shops and offices featured a neon advertisement, which helped create real forms and dynamic lines with electric lighting that complemented modern architecture’s “purified” facades, remarked Janet Ward[8]. Furthermore, the neon advertisement amplified the cinematic display of the goods shown in the windows. At that point, the shift from printed to electronic media of information took place, marking a pivotal moment in modernity that laid the groundwork for all the electronic media we recognise today[9].

By the way, the neon on the skyscraper’s facade was specifically designed for this architectural project by Warsaw Neon Workshop[10]. Archival photos reveal a large neon sign installed at the top of the building. It belonged to the local Galician oil company, “Polmin”, which had its headquarters in the same building, and a refinery located in the nearby town of Drohobych.

Not only the facade, but also the interior of the building creates a mesmerising atmosphere. Using the 3D scan model, one can enter the building through the central entrance, greeted by art deco lanterns and brass doors. At the entrance, there is a wooden vestibule, whose warm appearance sharply contrasts with the cold, shiny surfaces of the central lobby and main staircase.

We enter the shining spaces through the glass door handles of the second vestibule door. The walls of the lobby and staircase are entirely covered with alabaster, and the flooring is marble.

According to archival records, Ludwik Tyrowicz’s Stone and Marble Works firm was responsible for these surfaces[11]. The same firm also made travertine panelling for the building’s facade. Both stones were local. The marble from Kielcy town (south Poland) and alabaster from Zurawno (Lviv region). The newspaper “Chwila” admits that not only the materials but all the craftsmen working on the Sprecher “skyscraper” were local[12]. Considering the global economic crisis of 1929, which also greatly affected Lviv, the use of local materials and workers was more economical and aided Lviv’s development.

Moving further into the virtual 3D space, one observes the central staircase. The 3D scan allows us to view the stairwell comprehensively from above. The staircase features an elongated oval shape with light chrome bannisters, now covered in heavy oil paint. On each floor, there are two vertical windows on either side of the staircase, fitted with semi-transparent “milky glass”. These windows were not intended to increase light, as they face a deep, narrow courtyard. The semi-transparent glass was used to prevent viewers from seeing the dirt in the courtyard.

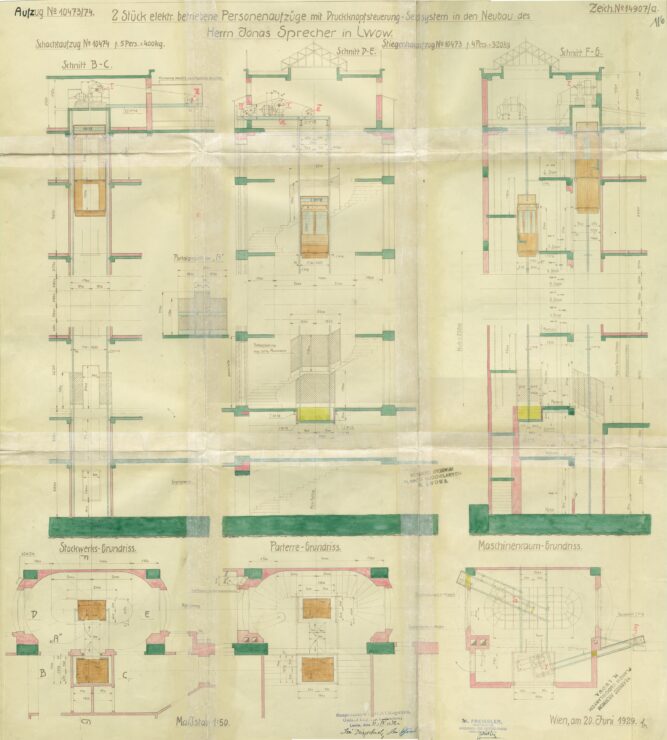

The primary natural light source in this space was a skylight made from luksfer blocks (glass bricks). Currently, the skylight no longer functions, and the glass blocks are covered with paint. As a result, the staircase remains quite dark during the day. The skylight not only illuminated the stairwell but also the lift located in the center of the staircase, which was mostly made of glass.

Due to the transparency of surfaces and lighting, the visitor, who goes with the elevator or walks the stairs, is simultaneously in several spaces at once, like in the case of a viewer of vitrines from the outside. Hence, the boundaries between the spaces where you actually are and the space you want to be were again completely blurred. There is no one reality anymore, but the reality simulation. The entire concept behind the Sprecher “skyscraper” and similar commercial buildings of that time, was in Lviv or Berlin, for example, about which Janet Ward writes in her research[14], was to sell a new virtual world—a promise of progress and desire, much like how the smartphone does today.

Another thing that connects the history of this building and contemporary times is the beauty industry. Among the offers in the Sprecher skyscraper was the Institute of Contemporary Cosmetics “Czar” (Instytut Kosmetyki Nowoczesnej “Czar”), led by Emilia Goldówna. As advertised, it was equipped with the most up-to-date medical equipment[15]. It is important to admit that the contemporary beauty industry started exactly in the 1920s and 1930s. In modernist times, not only facades and interiors were turned to plain and shiny, but also women’s bodies, as Kracauer notes: “The body has come to the surface and not only the body, but everything that is in and around it— the entire person from head to toe”[16]. Women were the main clients in the new shops and a target for the cosmetic industry. On one side, it was a sign of women’s liberation, which at the beginning of 20 century gave women the possibility to work and have their own money, but on the other side, women were considered as part of a commodity and most of the fashion or cosmetic shops were advertising that their products would enhance women’s attractiveness to men.

Coming back to the space itself, except for shops and offices, the building also housed luxury flats on the third to fifth floors. Apartments had from 5 to 8 rooms with panoramic views of the city center. One of the inhabitants was a famous Lviv painter Fryderyk Kleinmann[17]. Together with Kazimierz Sichulski, another well-known Lviv artist, he created a gallery of caricatures of writers and artists in the Atlas restaurant in Lviv. In the 1930s, he mainly devoted himself to painting and stage design, as well as designing costumes and puppets for theatres in Lviv: the Semafor satirical theatre, the Jewish Theatre, and the Azazel and Ararat theatres in Warsaw[18].

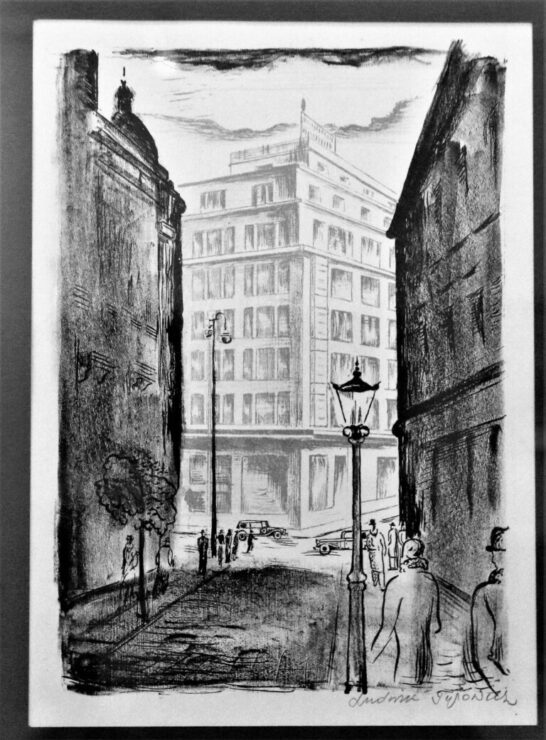

However, for many Lviv artists, living in the Sprecher skyscraper was not affordable. Even though this building was attracting many of them. This consumerist Mecca presented modernist forms and a new world for inspired painters, photographers, and philosophers. For example, the Sprecher “skyscraper” became a central figure in one of the famous lithographs of Lviv avant-garde painter and graphic artist Ludwik Tyrowicz. He was part of the Lviv avant-garde Association of Visual Artists – Artes and worked with themes of urban landscape. In 1932, he created a series of lithographs called “Beautiful Lviv” and, of course, he couldn’t omit the most prominent representative of its time – the Sprecher “skyscraper”. According to Polish researcher Jerzy S. Majewski, Tyrowicz also participated in the design process for the building’s facade[19].

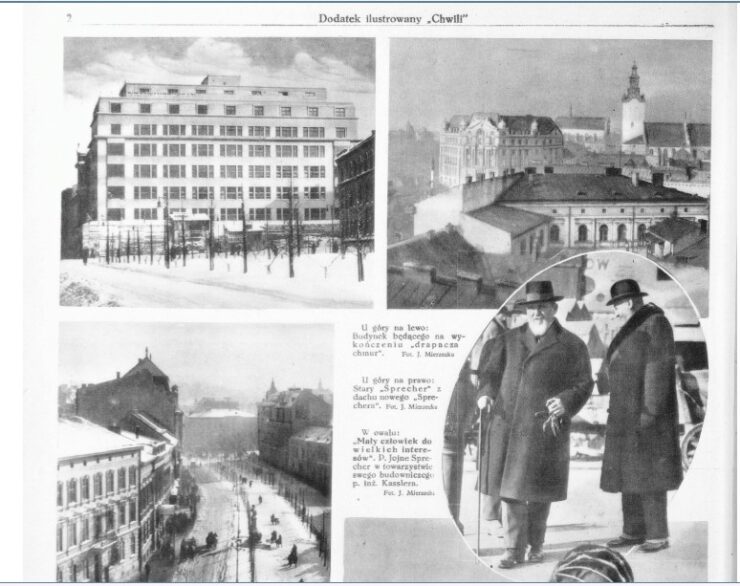

Not only the building but the owner and sponsor of modernist architecture, Jonasz Sprecher, was interesting for representatives of Lviv avant-garde circles. In the “Chwilla” from 1930, there are photos made by prominent Lviv photographer Janina Mierzecka, which show Jonasz Sprecher (on the left) and architect Kessler (on the right) standing together in front of the skyscraper[20]. There are also three pictures which portray a view of the building itself and two views from the building of another Sprecher “skyscraper”, designed by Kassler too in 1912. Through this photo, Mierzecka showed the connection of these two architectural objects, continuity, but also the stylistic evolution of Ferdynand Kassler’s architectural creations. These photos of Mierzecka are unique as they are not so much known architectural photography of the artist, which portrays Lviv.

Taking into account all these facts, we can assume that Lviv artists were connected with businessman Sprecher, or at least had an interest in his architectural investments. But who was Sprecher? Unfortunately, we don’t know much about this prominent Lviv figure. From local newspapers, we can learn that he was a multimillionaire. Sprecher was an industrialist and a real estate businessman, and as he himself said, “he built houses that no one could have dreamed of a few decades or even a dozen years ago”[21]. It’s hard to say if he was interested in modernist architecture because of its concepts and principles or only in the money those modernist skyscrapers were bringing him.

Besides dealing with modernist architecture, Sprecher led a fairly conservative, traditional life. He was religious and attended Synagogue every week[22]. The building investment was a family business, which is why he was always sharing responsibilities with his wife, Gizela, and his son Wilhelm. Most of the housing projects, which Sprecher commissioned, were signed by him and his wife.

In an interview with the newspaper “Chwila” in 1927, Sprecher speaks about his plans to build the second, modernist skyscraper, and that he is very much attached to the city: “I own a dozen or so tenement houses in Lviv, and just yesterday I bought a plot of land for a new building on Akademiczna Street… I have numerous expenses, taxes, the upkeep of around 20 guards, and children…I don’t like to travel, I’ve never left Lviv… I stick to the belief that home is the best place. At least a man can keep an eye on his own property.”[23]

Neither Sprecher nor Kassler refused to leave Lviv before and during the Nazi occupation. They decided to stay until the very end with their city and community, which they created. Both of them were killed during the Holocaust in Lviv[24]. After the war, the Soviets nationalized the Sprecher skyscraper: instead of neon advertisements, they put a party slogan on the facade. The building became the Trade Union Headquarters, where everyone acted as if the trade unions were playing a role in the totalitarian state. When Ukraine acquired independence, commercial uses returned, doors were always open, and the building was open to the public. When the russian full-scale invasion broke out, the doors of this magnificent building closed again. A military organization moved in: instead of office signs, they hung a portrait of their dead comrade at the main entrance door and banned anyone from entering the building.

So, the only opportunity today to visit the building from the inside is a virtual one. Using the 3d scans, we can walk through the building interiors, keeping in mind how the materials in interiors and exteriors were playing with an imaginary world since the building was built, and thinking about how many lives and ideas were intertwined in this architectural creation.

Research, text: Myroslava Liakhovych

Scanning and modelling: made by Paulina Marchenko, Maria Haiboniuk, Illia Oizer, Georgij Maksymenko, Oleksandr Podolskyj Oleksandr Holovashkin, Sofia Holz (Kharkiv School of Architecture). Fedir Ilkiv, Eugenii Kalchuk, Maksym Oholiev, Yana Kostiusheva, (Skeiron).

Sources and literature:

[1] Co dzień przynosi? Lwów nowy i stary, Nowiny poranne №63 18.08.1932

[2] State Archive of Lviv Oblast 2/1/42

[3] See note 2

[4] Czy lwowski „drapacz chmur“grozi zawaleniem ?, Chwila №3438/ 18.10.1928

[5] Ward, Janet, Weimar Surfaces. Urban Visual Culture in Weimar in 1920s Germany, University of California Press Berkeley/London 2001, p. 191-195

[6] See note 5

[7] State Archive of Lviv Oblast 2/1/44

[8] Ward, Janet, Weimar Surfaces. Urban Visual Culture in Weimar in 1920s Germany, University of California Press Berkeley/London 2001, p. 103-104

[9] See note 8

[10] See note 7

[11] See note 2

[12] Chwila №4055/ 10.07.1930

[13] See note 7

[14] Ward, Janet, Weimar Surfaces. Urban Visual Culture in Weimar in 1920s Germany, University of California Press Berkeley/London 2001, p. 153, 234

[15] Kosmetyka nowoczesna, №33/1936

[16] Neue Frauen zwischen den Zeiten, ed. Petra Bock and Katja Koblitz (Berlin: Edition Hentrich, 1995), 15.

[17] https://lia.lvivcenter.org/en/storymaps/100-addresses-mobile/

[18] Kleinman Fryderyk, [w:] Jolanta Maurin Białostocka, Janusz Derwojed (red.), Słownik artystów polskich i obcych w Polsce działających: malarze, rzeźbiarze, graficy, t. IV Kl-La, Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1971, s. 7

[19] https://miastarytm.pl/lwow-zycie-codzienne-miasta-w-czasach-sowieckich/

[20] Chwila. Dodatek ilustrowany, №7 Дата: 09.03.1930

[21] https://zbruc.eu/node/106196

[22] Sprawiedliwość, №262/ 29.10.1932

[23] See note 21